John W. Diamond, Ph.D.

Edward A. and Hermena Hancock Kelly Fellow in Public Finance

and Autumn Engebretson, Student Intern

What is the BCA?

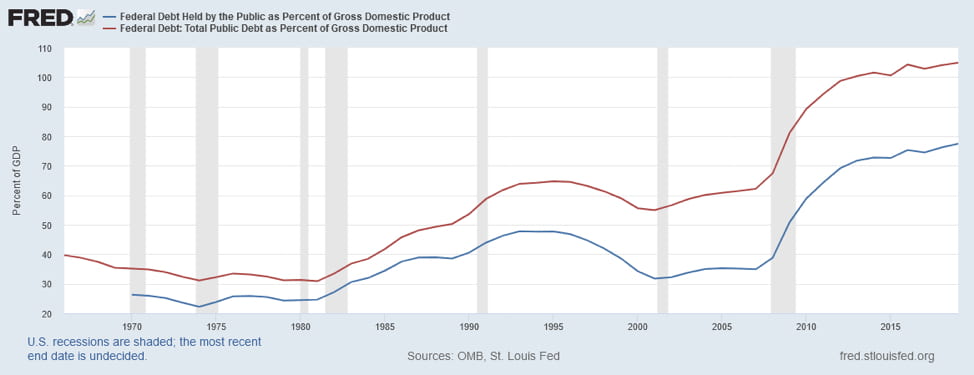

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) was enacted in response to the United States debt-ceiling crisis of 2011. In the last several decades, increases in the debt ceiling normally occurred without debate. However, the significant and rapid growth in the federal budget deficit and debt following the Great Recession led to calls for a reduction in the level of government spending. In 2011, the deficit as a percent of GDP was 8.4 percent, after peaking at 9.8 percent in 2009. Figure 1 shows that debt as a share of GDP had risen from 38.7 percent in 2008 to 64.3 percent in 2011.[1] Many politicians and pundits argued that without intervention that the US debt would continue to grow as a share of GDP and have adverse effects on US economic growth. The debt-ceiling crisis centered on the argument made by House republicans that in exchange for an increase in the debt ceiling the president would have to agree to a reduction in government spending and the federal deficit. Note, however, that there was bipartisan concern about the level of federal budget deficits and debt. As shown by the vote on H.R. 1954 (a bill to increase the debt ceiling as President Obama requested) on May 31, 2011, which failed by a vote of 318 to 97 with 236 Republicans and 82 Democrats voting against the bill.[2]

Figure 1

The BCA increased the debt ceiling by $400 billion in August 2011, and allowed President Obama to request additional increases of $500 billion and $1.2 trillion. The BCA included $917 billion in direct spending reductions over 10 years to offset the initial increase of $900 billion in the debt ceiling, with only $21 billion of the increase occurring in 2012. The $1.2 trillion increase in the debt ceiling was contingent on efforts to reduce the spending by an equal amount. Thus, the BCA created the Joint Committee of Deficit Reduction, required a vote on a balanced budget amendment, and stipulated across-the-board cuts to mandatory and discretionary spending if Congress failed to act to offset the $1.2 trillion increase in the debt ceiling. This effort to reduce federal government spending relied on discretionary spending caps and automatic reductions in mandatory spending. Total reductions were to equal $1.2 trillion after debt service cost reductions ($216 billion) and nine years of annual cuts to defense ($55 billion per year) and non-defense ($55 billion per year) spending.[3]

The discretionary spending caps from FY2012 to FY2021 effectively set the maximum amount of appropriated spending that Congress could pass. Sequestration was the enforcement mechanism such that if spending exceeded the caps it automatically triggered spending reductions. Because discretionary spending is almost evenly split between defense and non-defense spending and there were significant exemptions in the nondefense category,[4] the spending cuts placed a disproportionate burden on defense spending. The BCA implemented the mandatory spending caps suggested by the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (often referred to as Simpson-Bowles).

Under the BCA, the sequester could have been avoided if Congress passed legislation by January 15, 2012 to reduce the deficit by $1.2 trillion from FY2012 to FY 2021, but this was not accomplished and the process of automatic spending reduction (i.e., sequestration) began January 2, 2013 but was quickly postponed to March 1 by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA). Spending reductions were to be split evenly between defense and nondefense spending, and exempt accounts included Social Security and the Department of Veterans Affairs.[5] Because of the exemptions to large budget items, the effect on the non-exempt programs were disproportionately large; the reduction in discretionary defense spending was 9.8 percent in FY2014 and the reduction in non-defense spending was 7.4 percent.[6]

Certain areas of spending are not subject to the limits put in place by the BCA. Two such areas are Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) and emergency spending (spending for the Global War on Terrorism fits under the OCO category). Disaster relief, wildfire suppression, and safeguards to fraud and abuse are also not subject to limits.[7] Exempting these items allowed for quick fiscal action in emergencies and limited the long-term budgetary effects of single events requiring government outlays.

What legislation has occurred since the BCA?

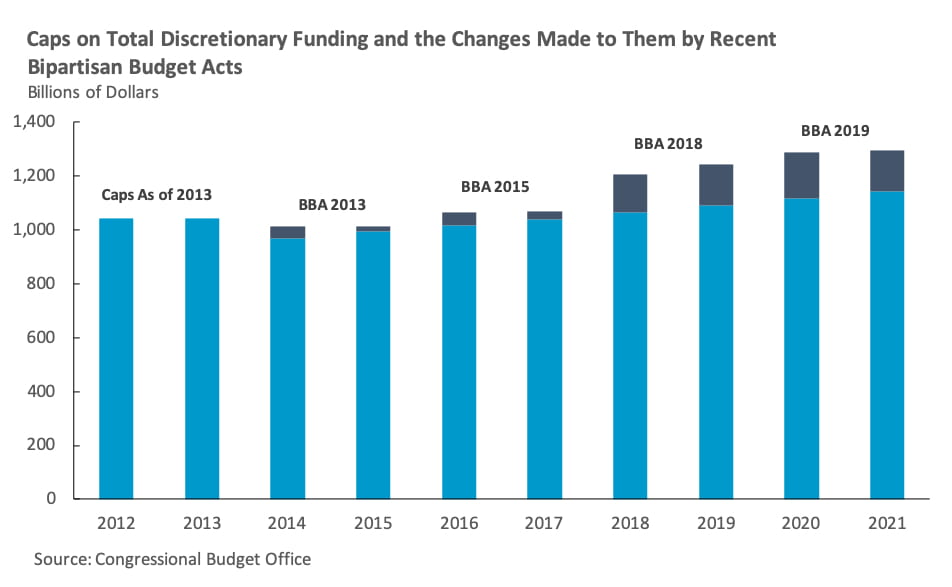

Since the passage of the BCA there have been five significant pieces of legislation that have altered the timing of the planned reductions in the deficit. The five significant legislative acts include the ATRA, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019).[8] All of these pieces of legislation increased limits in spending, although with varied effects on the overall efficacy of the measures put in place by the BCA.

The ATRA made significant changes to the BCA, postponing any potential sequestration from occurring from January 2, 2013 to March 1, 2013. Enforcement of discretionary spending limits was also postponed to March 27, 2013. In total, this reduced BCA spending reductions by $8 billion split evenly across defense and non-defense for FY2013 and FY2014.[9] The sequester was also reduced in size from $109 billion to $85 billion, which was counteracted by further spending cap reductions and changes in retirement account revenues.[10]

The BBA 2013, approved in December 2013, revised spending caps for defense and nondefense categories upwards by $22.4 billion for FY2014 and by $9 billion for FY2015. It also extended sequestration through FY2023 for mandatory spending categories. Spending cap increases were offset by changes in retirement accounts, reduced cost-of-living (COL) adjustments, and other minor policy changes.[11]

The BBA 2015, approved in November 2015, suspended the debt ceiling through March 2017 and increased BCA discretionary limits in 2016 by $50 billion and in 2017 by $30 billion, split equally between defense and nondefense spending. To offset these increases, sequestration was extended an additional year to 2025, Medicare reimbursements were lowered, and other changes were made to compliance measures.[12]

The BBA 2018, signed by President Trump in February 2018, raised BCA discretionary limits in 2018 and 2019 by a total of $242.4 billion, $165 billion of which was in defense. Mandatory spending reductions were also extended, with reductions disproportionately affecting nondefense spending.[13]

The BBA 2019, signed by President Trump in August 2019, raised BCA discretionary limits from $1.12 trillion in 2020 to $1.29 trillion, and from $1.15 trillion in 2021 to $1.30 trillion. This specifically increased defense spending by $90 billion and nondefense by $78 billion in 2020 and established higher OCO targets at $80 billion for 2020 and $77 billion in 2021. The BBA 2019 also extended the sequester for another two years to FY2029, estimated to reduce the FY2019-FY2029 budget deficit by a further $62 billion. Finally, the debt limit was suspended through August 2021.[14]

What were the effects of the BCA?

The BCA resulted in the activation of the sequestration process in 2012, to be implemented January 2013 (later extended to March by the ATRA). The Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reductions was unable to reach an agreement on further budgetary cuts, therefore a $1.2 trillion automatic cut was implemented. Reductions in the cost of servicing the debt account for 18 percent of the $1.2 trillion. The remainder was spread from FY2013 to FY2021 and evenly distributed across defense and nondefense spending, resulting in a $54.7 billion reduction per category per year. Medicare was limited to a 2 percent reduction.[15] Changes to the duration and levels of the sequester by year are discussed above in reference to the subsequent legislation.

A concern with regard to defense spending is that, rather than adhering to the spending caps put in place, the Department of Defense would reallocate spending to the OCO category, which was not subject to the spending caps. Spending related to OCO is hard to define and monitor leaving significant opportunity for abuse through over allocating spending to the OCO category rather than discretionary defense spending. This would allow the defense sector to avoid a portion of the spending reductions required by the BCA. However, many of these concerns have not materialized, due in part to the general trend of scaling down military action in the Middle East. OCO spending itself has been falling, from a peak of $194.6 billion in 2008 (28 percent of total defense spending) to $126.5 billion in 2012 (18 percent of total defense spending), and $72.5 billion in 2015 (11 percent of total defense spending). OCO spending has picked up slightly since then, rising to $103.4 billion in 2017 (14 percent of total defense spending) before falling to approximately $77 billion in both 2018 and 2019 (10 percent of total defense spending). The majority (92 percent) of this spending is by the Department of Defense, with USAID and Homeland Security making up the remaining portion. [16]

However, in the FY2020 proposed budget, OCO spending more than doubled over the previous year to $165 billion. It was explicitly stated that this dramatic increase was intended to make up for cuts to the defense budget from the BCA, with compensatory decreases in OCO and increases in discretionary spending beginning in 2022 after the expiration of the BCA.[17] This led to significant backlash from fiscal conservatives, as it legitimized many of the concerns regarding the OCO spending category that have existed since its exemption from the BCA. This supports the need for more effective regulations regarding the use of OCO or its inclusion in future budgetary limits, as the scale of abuse can be large from this category of spending.

A similar argument could be made with regard to emergency spending, which was not subject to the spending caps put in place by the BCA. However, due to the well-defined nature of this category of spending, there have been few concerns of abuse.

Why is this relevant now?

Examining the BCA is relevant now given the enormous fiscal policy measures enacted to support businesses and individuals since the onset of the on-going COVID-19 pandemic. Obviously, these efforts were necessary to avoid a major contraction in the US economy, but will also significantly increase the level of the debt to GDP.

Congress continues to debate additional stimulus measures as the economic dislocations caused by the pandemic persist. Thus, federal deficits and debt are continuing to grow at a record pace. However, eventually U.S. fiscal policy must move toward a more sustainable path. Does the BCA provide us with a framework for curtailing unsustainable deficits and moving to a sustainable fiscal policy? Note that discretionary spending caps put in place by the BCA are nearing their expiration dates. Overall, the BCA seems to be a colossal failure as a tool for controlling spending. Since 2013, Congress has passed a series of two-year deals to avoid most of the cuts imposed by the BCA. In addition, Congress changed the way that they dealt with the debt ceiling. For example, in 2011 when the BCA was implemented Congress raised the debt ceiling by a specific amount, such as $2.1 trillion under certain circumstances. However, since 2013 Congress has begun suspending the debt ceiling – so that during the suspension period there is no operative ceiling on the debt at all. While the debt ceiling is a rather useless budget tool, it is clear that Congress has no appetite for any kind of constraint on its spending authority. Neither the BCA nor the debt ceiling limit Congress’s ability or will to spend money that is financed with debt (i.e., revenues from future generations). To say that the BCA was ineffective and that it failed to accomplish its original goal is likely an understatement.

Figure 2

Sequestration itself is also controversial, as it is a relatively crude method of budget reductions. It is applied evenly across budget areas, forcing agencies to apply reductions across non-exempt programs. One line of thought praises the imprecise nature of the sequester as a further disincentive to exceed spending caps; others claim that the sequester should be well designed for practical reductions so that if it is reached, it can be better administered and have less distortive effects.[18] It is important to consider the criticisms of the sequestration process and perhaps develop a more fine-tuned system of budgetary reduction that still serves to encourage programs to adhere to lower spending limits.

Conclusion

The United States has had a history of inconsistent attitudes with regard to the budget deficit and federal debt. Candidates and parties often campaign on a promise of PAYGO (pay as you go in regards to funding new spending or tax reductions) or austerity that are rarely realized once in office. The COVID crisis was a black swan event that required significant government action, and there is a consensus around the necessity of a significant amount of the government action that was taken mitigate the economic effects of the pandemic. Nevertheless, it is important to reflect on the BCA, especially as it nears expiry and Congress and President Biden must decide on whether to enact similar legislation moving forward. There have been substantial impacts of the BCA, centrally on reducing growth in the defense budget, but it was likely the result of a greater trend of demilitarization rather than the efficacy of the BCA. The repeated extensions and modifications through additional legislation indicate that the BCA has not been a particularly effective budgetary tool in capping spending. In any case, curbing large increases in federal spending for discretionary and non-discretionary programs will continue to be an important fiscal issue, and efficient and effective policy changes to address unsustainable fiscal trends is critical for the continued economic growth and increases in the standard of living for future generations.

Footnotes

[1] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFSGDA188S

[2] https://www.congress.gov/112/crec/2011/05/31/CREC-2011-05-31.pdf (H3783).

[3] Levit, Mindy R. “The Budget Control Act of 2011: Budgetary Effects of Proposals to Replace the FY2013 Sequester.” Congressional Research Service, December 21, 2012, 13.

[4] Driessen, Grant A, Molly F Sherlock, and Donald J Marples. “Debt and Deficits: Spending, Revenue, and Economic Growth.” Congressional Research Service, December 4, 2018, 3.

[5] Heniff, Bill. “The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012: Modifications to the Budget Enforcement Procedures in the Budget Control Act.” Congressional Research Service, February 4, 2013, 5.

[6] Levit, Mindy R. “The Budget Control Act of 2011: Budgetary Effects of Proposals to Replace the FY2013 Sequester.” Congressional Research Service, December 21, 2012, 13.

[7] Lynch, Megan S. “Exceptions to the Budget Control Act’s Discretionary Spending Limits.” Congressional Research Service, June 19, 2019, 18.

[8] Driessen, Grant A. “Budgetary Effects of the BCA as Amended: The ‘Parity Principle.’” Congressional Research Service, February 23, 2018, 3.

[9] Heniff, Bill. “The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012: Modifications to the Budget Enforcement Procedures in the Budget Control Act.” Congressional Research Service, February 4, 2013, 5.

[10] Austin, D Andrew. “The Budget Control Act and Trends in Discretionary Spending.” Congressional Research Service, November 26, 2014, 12.

[11] Austin, D Andrew. “The Budget Control Act and Trends in Discretionary Spending.” Congressional Research Service, November 26, 2014, 13.

[12] Peter G Peterson Foundation. “Analysis: Understanding the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015,” November 17, 2015. https://www.pgpf.org/analysis/understanding-the-bipartisan-budget-act-of-2015.

[13] Driessen, Grant A. “Budgetary Effects of the BCA as Amended: The ‘Parity Principle.’” Congressional Research Service, February 23, 2018, 3.

[14] Driessen, Grant A, and Megan S Lynch. “The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019: Changes to the BCA and Debt Limit,” August 5, 2019, 4.

[15] Driessen, Grant A, and Marc Labonte. “The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects.” Congressional Research Service, December 29, 2015, 24.

[16] McGarry, Brendan W, and Emily M Morgenstern. “Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status.” Congressional Research Service, September 6, 2019, 52.

[17] McGarry, Brendan W, and Emily M Morgenstern. “Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status.” Congressional Research Service, September 6, 2019, 52.

[18] Lynch, Megan S. “Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions.” Congressional Research Service, December 1, 2015, 8.