Immigration has been a heavily debated topic in the last few years, and it has become the center of many candidate platforms for the upcoming presidential elections. However, the unaccompanied alien children (UAC) crossing the southern border constitute an important policy issue that most presidential candidates have not factored into their discourse. How should the U.S. and Mexico create specific policies for those who are not yet adults?

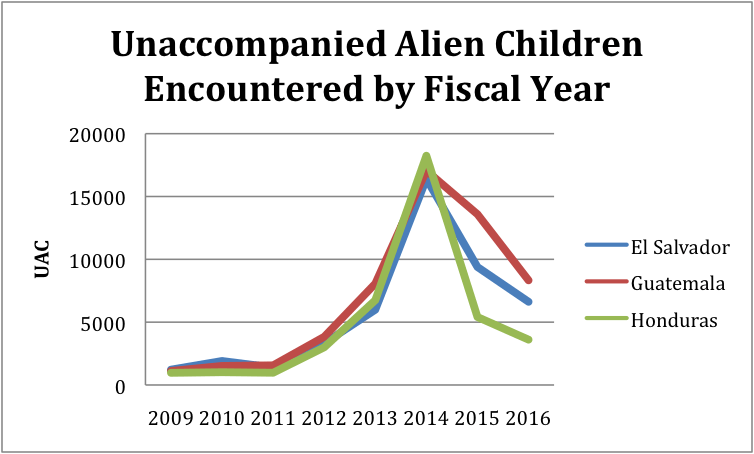

In 2014, the United States alone saw a record 51,705 unaccompanied alien children arrive from Central America. The majority of those children came from the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. Most of them were over the age of 13, although recently there has been a drastic increase in migrations of UAC ages 12 and younger. In comparison, 2012 and 2013 reported only 10,146 and 20,805 UAC, respectively, coming from Central America.

One of the main reasons for this increase is that “coyotes” — or illegal smugglers — give many child migrants the false pretense that once they reach the U.S., they will be given refugee status and allowed to stay. Coyotes charge anywhere from $400 to upward of $1600, with the promise that these children will make it into America without consequences. In addition, in a survey conducted by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, immigrant children indicated that their main decision for leaving is because “they had been personally affected by the violence in their region by organized armed criminal actors, including drug cartels, gangs and State actors.”

With the 2014 influx of UAC, the United States border institutions and nongovernmental agencies saw cracks in their system. They were unprepared to manage and provide care for these immigrants as mandated by U.S. laws. Due to these issues, the Obama administration created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, and the U.S. Senate passed immigration reform bill S.744. Under the DACA program, children under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012, who came to the U.S. before their 16th birthday, are either currently in school, have graduated or obtained a certificate, have not committed a felony, and have continually resided in the U.S. may apply to defer removal action. In addition, the reform bill’s main goal was to provide a legal path for lawful permanent residence for all undocumented immigrants.

Furthermore, the program requires that all alien children in the U.S. receive screening as potential human trafficking victims. They are to be inspected for medical and health issues, in addition to being provided with housing during the screening process. The Obama administration pushed for U.S. institutions to be better prepared by asking Congress for nearly $4 billion to help ease this problem. Today, the number of UAC has slightly decreased, with only 18,558 UAC from Central America detained while trying to enter the U.S. illegally in 2016. Nonetheless, this is not because the children’s living conditions have improved in their home countries. Many have theorized that the U.S. has put political pressure on Mexico and the Northern Triangle countries to push for policies that decrease migration.

With a decrease in the number of children making it the U.S., Mexico is now dealing with the issue. In 2015, Mexico’s apprehensions of children coming from the Northern Triangle rose from hundreds to thousands. Mexico is not well prepared to handle these growing numbers. For the first time in history, more children were detained at the Mexico-Guatemala border than at the Mexico-U.S. border. Mexico has only recently started to set up policies like those available in the U.S. Mexico’s Southern Border Plan, created in 2014, was established with the goal of creating order in Mexico’s southern region in terms of migration, while also protecting human rights. The expectation is that enhanced border security efforts will consequently dissuade immigrants from making the trip north.

In addition, many nongovernmental organizations are working in conjunction with the Mexican government to try to alleviate the problem and create a framework to deal with the unaccompanied children. For example, UNICEF recently conducted a course for consulate representatives in Mexico to help them acquire tools for better approaching unaccompanied child migrants. The Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs, also in coordination with UNICEF, presented a protocol to detect signs of international protection needs, including asylum and subsidiary protection. This topic has to be treated in terms of bilateral policy with joint ventures between the U.S. and Mexico.

Immigration is not just an issue for the U.S. to deal with. It requires the U.S. and Mexico to work together, alongside the countries in the Northern Triangle, to regulate and/or address the flow of Central American children migrants passing through both countries.

Source: U.S. Department of State. Author’s own elaboration.

Source: U.S. Department of State. Author’s own elaboration.

Marcela Benavides is a research intern at the Baker Institute Mexico Center. She is a Rice University junior double majoring in political science and Latin American studies, with a minor in business administration.