As a presidential candidate, Enrique Peña Nieto (PRI) claimed he would bring a new strategy to the country’s struggle with organized crime — one that de-emphasized the targeting of drug kingpins and focused on reducing homicides, extortion cases and kidnappings.

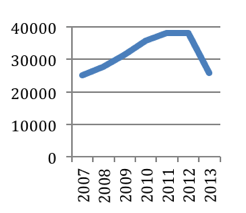

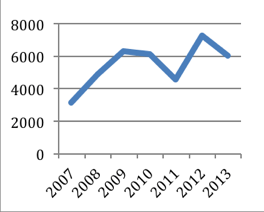

One year into the presidency, Peña Nieto’s administration claims that the homicide rate has dropped by 18 percent; on the other hand, government stats point to a 35 percent increase in kidnappings. After the arrest of two major Zeta and Gulf Cartel leaders earlier this year, Peña Nieto’s strategy shift appears to be more rhetorical than real. Many scholars, analysts and civil society leaders have taken issue with the claim that drug-related violence has declined. Recognizing the importance of understanding drug-related violence in Mexico, Baker Institute Viewpoints invited five scholars to respond to the question, “Has drug violence in Mexico declined?”

Read other posts in this series:

- In Mexico, security is in the eye of the beholder by Sylvia Longmire, former Air Force officer and special agent with the Air Force Office of Special Investigations

- Perception and intent define the reality, but criminal violence in Mexico has metastasized by Robert Bunker, senior fellow with Small Wars Journal — El Centro

- Measuring mayhem: The challenge of assessing violence and insecurity in Mexico by John Sullivan, lieutenant in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department

- Mexico’s national crime statistics show no significant decline in homicides and disappearances by Molly Molloy, research librarian and border specialist at the New Mexico State University Library

In the last installment, Baker Institute drug policy fellow Nathan Jones addresses the increase in kidnapping and extortion in Mexico.

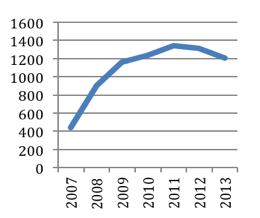

The answer to the question, “Has drug violence in Mexico declined?” depends on what drug-related violence we care about the most. In general, homicides are down by 18 percent (if one trusts the government’s numbers — Molly Molloy in the previous piece wrote a thorough analysis of homicide statistics), but kidnappings and extortion cases are up by 35 percent. The latter are high-impact crimes that touch the state and society in particularly vulnerable spots. For the state, these crimes are a derogation of its fundamental duty to provide security for its citizens. For society, the psychological impact of kidnapping is extreme, and unlike previous iterations of Mexican drug trafficking, legal businesses are now subject to extortion demands from local mafias as they diversify their criminal activities.

[Data for 2013 is through September.]

Kidnapping and extortion

Many of these extortion demands are enforced through the threat of kidnapping. While kidnappings in Tijuana tend to precede homicide surges, at the national level, kidnapping and extortion appear to lag behind homicides. The greatest surges in homicides occur when the largest trafficking networks engage in violent conflict. They kill each other and innocent bystanders en masse as they struggle to gain control of important plazas (trafficking corridors) such as Tijuana from 2008 to 2010, Nuevo Laredo from 2004 to 2007, and Juarez from 2008 to 2012. Following these conflicts, kidnapping rises in popularity. It is structurally determined in the sense that the conflicts between cartels produce newly fragmented cells with scant ability to traffic drugs and maintain drug source contacts. Profit-starved, the cells diversify into other criminal activities such as extortion and kidnapping to maintain their payrolls. In one sense, it represents an evolution of organized crime — but evolution should not be conflated with progress. The individuals and organized crime groups that diversify into crimes such as kidnapping tend to be lower on the criminal profitability scale. They draw the greatest ire from the state by “heating up the plazas” — which in turn leads to stronger reactions against them from the state. The Mexican government is cracking down on the most territorial cartels, hoping to reduce the level of violence.

In the long term, I am optimistic about the situation. In my dissertation I chronicled how territorial drug networks in Tijuana were systematically targeted by a de facto alliance of trafficking-oriented networks, civil society and the various state security apparatuses. I think this will play out more broadly in Mexico, but over a longer time frame than in Tijuana. In the long run, corruption will be a greater problem as trafficking groups with high profits and political connections not only survive but thrive.

Addressing drug-related violence in Mexico

In some respects, Mexico is already crafting policies that will reduce violence; in other respects, it is rejecting some of the most important policies that can potentially mitigate violence. The administrations of both Enrique Peña Nieto and Felipe Calderon recognized the need for judicial reform and capacity building in the law enforcement and judicial system. Resolving less than two percent of crimes results in a level of impunity that is far too high and encourages further crime. Beyond judicial reform, coordination across agencies and geographic territories will also be important.

Drug policy reform

Supporting change in the drug prohibition regime could significantly reduce drug cartel profits. As Mexico attempts to improve institutional frameworks to reduce violence, it suffers from the scourge of corruption that in turn hinders these reforms. In this sense, institutional strengthening and drug policy reform cannot be divorced. Peña Nieto has said that he is open to a debate on marijuana legalization, but that he is personally against it. Hopefully he will listen to the numerous voices of leaders in Mexico — such as former President Vicente Fox and Ernesto Zedillo — who are calling for graduated drug policy reforms in Mexico, including decriminalization policies.

Mexico is not the only country calling for drug reform. Across the hemisphere, leaders and grassroots movements are pushing for change. In the U.S. consumer market, Colorado and Washington have legalized marijuana, while 20 other states and the District of Columbia allow medical use. President Otto Perez Molina of Guatemala, an increasingly important transit nation in the drug trade, has called for a commission to evaluate the country’s drug policy. In Colombia, which has long been an important source country, President Santos has made it clear that he too is open to reform by sponsoring OAS reports on drug reform. Uruguay may soon become the first nation to completely legalize marijuana. Peña Nieto may not be in favor of drug legalization now, but as the tide turns in the international debate, he may warm to it. Drug policy reform is the only way to address the underlying supply and demand forces funding these violent organized crime groups. Attacking their ability to corrupt will make institutional reforms to reduce violence more successful.

Data for the above charts came from SESNSP (Executive Secretariat of Public Security).

Nathan Jones is the Alfred C. Glassell III Postdoctoral Fellow in Drug Policy at the Baker Institute. His areas of interest include U.S.-Mexico security issues, illicit networks and cross-border flows. Follow him on Twitter at @natejudejones.

Nathan Jones is the Alfred C. Glassell III Postdoctoral Fellow in Drug Policy at the Baker Institute. His areas of interest include U.S.-Mexico security issues, illicit networks and cross-border flows. Follow him on Twitter at @natejudejones.