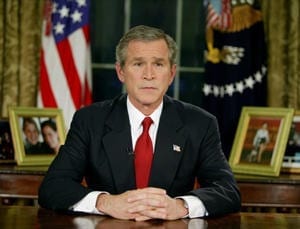

President George W. Bush announces the beginning of Operation Iraqi Freedom in a March 19, 2003, address to the nation.

In the second of a series of blogs leading up to the 10th anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Iraq on March 19, Baker Institute fellow Joe Barnes asks, “What are we to make of the plethora of justifications for the war?” The first blog in the series, “Learning the lessons of the Iraq War,” is available here.

Why did we invade Iraq? Let me count the ways …

The promoters of the war — inside and outside the administration of George W. Bush — put forth any number of justifications for the invasion. These arguments found their origins in a variety of positions: a humanitarian desire to overthrow an admittedly ruthless tyrant; a democratic urge to advance a “freedom agenda” in the Middle East, if necessary by force; a geopolitical drive to reshape the region in ways advantageous to the United States and our allies.

But first and foremost was the claim that the regime of Saddam Hussein was actively pursuing acquisition of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) — and, specifically, a nuclear bomb. National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice famously invoked the terrifying specter of a “mushroom cloud” in support of Bush administration policy toward Iraq. War supporters made much of “evidence” purporting to show an ongoing Iraqi nuclear program, notably purchases of “yellow-cake” uranium and aluminum tubing for centrifuges. The administration continued to assert the existence of a major Iraqi nuclear program even after International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors failed to discover evidence for one.

Interestingly, much of the purported evidence on Iraq’s nuclear and other WMD programs was at the time contested within the United States government itself and criticized by independent experts. But the evidence was nonetheless promoted relentlessly by supporters of the war. And it surely had its effect. Secretary of State Colin Powell’s speech to the UN Security Council detailing evidence of Iraq’s WMD program — a farrago of unjustified claims, selective evidence and overblown conclusions — was at the time widely hailed as a conclusive case for war; now Powell, rightly, calls the speech a “blot on his record.”

In any event, we went to war on false premises backed up by exaggerated rhetoric. Let me stipulate: we are not necessarily talking about conscious deceit. In trumpeting incomplete or ambiguous evidence about Iraq’s WMD programs, supporters of invasion were merely indulging in a universal human tendency to force facts into conformity with pre-existing notions. Once advocates of war decided that the regime of Saddam Hussein posed a threat so severe that it must be eliminated, it became easy to cherry pick evidence and to dismiss doubters. But, in the case of the Iraq War, this all-too-human weakness contributed to poor decision-making and a catastrophic outcome. The truth — that the evidence for a major Iraqi WMD program was, to put it charitably, scanty — stood in plain sight; war supporters simply refused to see it.

More generally, what are we to make of the plethora of justifications for the war? Not much. There is surely nothing intrinsically sinister about it. Decisions to go to war are rarely simple. They are driven by complex reasons of state and politics. But, from the Bush administration’s perspective, the multitude of justifications also served a very useful purpose in creating a domestic consensus — at least in terms of elites — in favor of invasion. Neoconservatives were excited by the prospect of reshaping the Middle East; liberal internationalists were willing to swallow their doubts about the Bush administration in order to topple a dictator; “small c” conservatives in the foreign policy establishment went along, at least in part, out of genuine (if misplaced) concerns about Iraq’s WMD programs.

In other words, there is plenty blame to go around. But there is no escaping the ultimate responsibility of the Bush administration and, above all, the president himself — a subject for another post.

Joe Barnes is the Baker Institute’s Bonner Means Baker Fellow. From 1979 to 1993, he was a career diplomat with the U.S. Department of State, serving in Europe, Africa, the Middle East and South Asia.