By Anna Mikulska, Ph.D.

Nonresident Fellow, Center for Energy Studies

and Kamila Pronińska, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Department for Strategic Studies and International Security, University of Warsaw

Even before Russian invasion on Ukraine, many have wondered what would happen if Russian gas stopped flowing to Europe either due to sanctions or due to Russia’s using natural gas supplies as energy weapon. The latter possibility was confirmed in late March when Vladimir Putin announced that payments for gas from “unfriendly” countries should be made in roubles or gas will stop flowing. He delivered on the promise when last week Poland and Bulgaria refused to pay in roubles for their contracted Russian supplies. But the circumstances of the gas cutoff to Poland and Bulgaria indicate that it may not necessarily become a typical occurrence for all Gazprom’s customers in Europe.

Poland, Bulgaria and Russian Gas: Closing Time

Russian supplies have accounted for a substantial portion of the domestic gas consumption in Poland and Bulgaria (45% and 90%, respectively), yet both countries have been vocal about the need for gaining independence from Russian suppliers and increasing EU’s strategic autonomy in relation to Russia since the very beginning of war in Ukraine. For both Poland and Bulgaria, long-term contracts with Russia are set to expire at the end of 2022. Hence, neither had plans to sign new long-term contracts with Gazprom, and both have been well on their way to ensure alternative supplies.

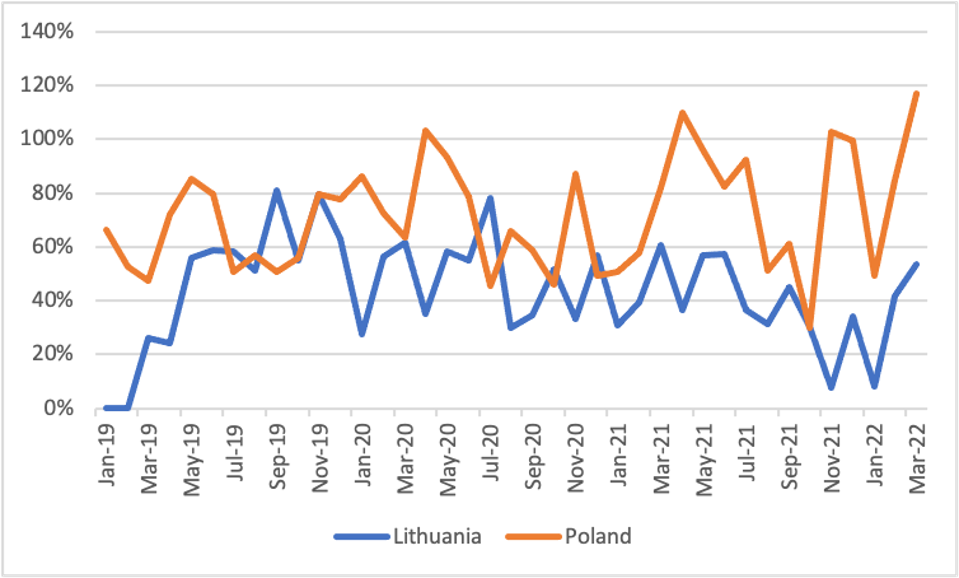

Poland has been working on its gas source diversification for years. The efforts resulted now in a functioning LNG import terminal (currently being expanded from 5 to 7.5 bcm annual capacity); a new pipeline to bring in gas from Norway to start working in October, reaching in January full capacity of 10 bcm/yr; as well as several interconnections, including one with Germany (1.5 bcm), one with Slovakia due to start working in the summer (5-6 bcm) and GIPL with Lithuania that began working May 1. The latter is especially significant as it connects the two LNG terminals that are functioning in Central and Eastern Europe. While the Polish terminal is generally highly utilized, Klaipeda has had less success (see Figure 1 below that shows monthly capacity utilization for both terminals since January 2019) but now can become a source of supply for Poland and other countries in the region, if needed. There is the possibility for adding another layer of supply security by sending additional gas supply to Latvia’s natural gas storage (2.3 bcm of active capacity) in Incukalns. In addition, Poland’s natural gas storage is currently filled at 76%, a level that is an exception with average gas storage in Europe now at below 30%.

Figure 1. LNG Import Terminals Capacity Utilization

Data Source: Cedigaz; authors’ analysis

Bulgaria has been somewhat less prepared. Its domestic gas storage is only 17% full and the country is not as well interconnected within the region. Nevertheless, a new interconnector with Greece (IGB) is due to start working in June to bring gas from Azerbaijan and regasified LNG from Greece. IGB pipeline projected capacity is 3 bcm/yr and can be expanded to 5 bcm/yr. It will be enough to fully replace Russian supplies. In the meantime, Greece has been reported to suggest possible reverse flows via the Turkish Stream.

What About Other Gazprom Customers in Europe?

Poland and Bulgaria refused Russia’s demand to pay in roubles for natural gas they receive from Gazprom. They saw such change as a breach of contract. Their decision has been predicated upon the general understanding that such payment would be in conflict with sanctions that the EU has imposed on Russia’s Central Bank.

Russia has proposed a gas-for-roubles scheme via accounts that needed to be opened in Gazprombank. This demand has been interpreted as an attempt to create loopholes in the sanctions regimes and divide the EU countries over whether such a transaction may or may not be in breach of EU sanctions. Potentially, if payment is made at the time of transfer of euros or dollars (per initial terms of contract) then there is a way in which one could argue that this is the end of the obligation and sanctions are not breached. The issue is not clear, however. And lack of transparent guidelines from the European Commission does not help. Hence, we may need to wait for new payments coming due to see how companies respond.

As of now, several countries signaled their potential willingness to work on terms of engagement with Russia, including Austria, Hungary and Germany. The latter, the EU’s largest importer of Russian gas, is in an especially difficult position: highly dependent on Russian gas with highly limited alternatives of ramping up alternative gas supplies at a moment’s notice. The country has not been prepared for the possibility of a Russian gas cutoff. On the contrary, until the day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine it has been setting up a system where Russian gas would remain the main component of their energy supply. And while Germany is scrambling to arrange liquified natural gas (LNG) supplies as soon as possible, it will not be until the end of this year when it can potentially bring them in by quickly setting up impromptu LNG terminals using Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRUs). Still, this will not be enough to substitute for the entire Russian gas imports, which reached a whopping 56 bcm in 2019 and 2020. Given German plans to phase out nuclear power this year and phase out coal by 2038 (and even 2030 according to the new coalition agreement), the country cannot afford to lose much of its natural gas supply. Indeed, its leaders have been underscoring that an immediate cutoff from Russian gas (in conjunction with an embargo on Russian coal and oil that Germany has all but been accepted now) could send the country’s economy into a sharp recession.

Russia’s demand of a rouble-for-gas scheme is a reaction to Western sanctions. It is also a well-known “divide and conquer” instrument of Russia’s energy politics and a test of the EU’s unity. Yet, the decision to suspend gas deliveries to Poland and Bulgaria has been also a preemptive move since both countries have announced that they will not renew long term contracts with Gazprom. The difference in total volumes and availability of alternative supply, as well as the smaller role that natural gas plays in the Polish and Bulgarian economies, make the decision both countries reached on payment a better one than a potentially risky bet on an untested transaction scheme.

Poland can actually seize on the cutoff by claiming leadership in the region not only in diversifying away from Russia but as a point of supply and energy security for the region, a role that Germany was hoping to perform with access to abundant supply of Russian gas via Nord Stream 1 and the now defunct Nord Stream 2. The Czech Republic has already restarted talks with Poland on the Stork II gas interconnector, which would provide a landlocked neighboring country access to the northern gas corridor, including LNG supplies via the Baltic terminals.

Countries that until now have been less concerned with dependency on Russia and allowed the latter accumulating market power will need to come up with a different strategy. This strategy will be crucial not only for their own sake but also for the sake of the EU economy and energy security. After all, an immediate withdrawal of Russian natural gas imports from Germany, Italy and/or other major gas importers with limited alternatives would likely have serious effects on the entire EU market. From the energy security perspective, the specifics of those countries’ decision will be important and need to represent a definitive, unifying statement that, as it stands, Russia is not a reliable provider of natural gas and the EU needs to diversify gas supplies away from Russia, if not abandon them altogether.

This article originally appeared in the Forbes blog on May 3, 2022.