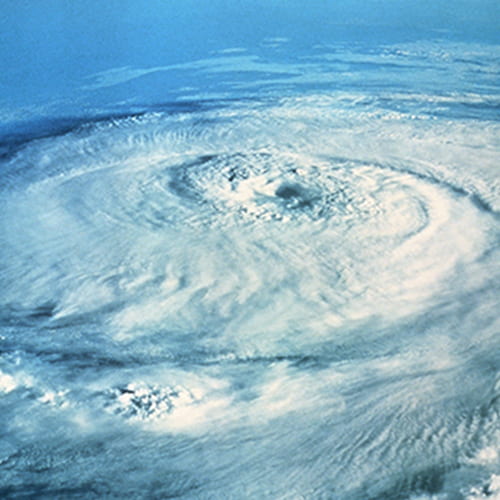

Hurricane Ida, the powerful storm that devastated Louisiana’s coastal communities last week, is a “prime example of a worst-case future for Houston,” says Rice Faculty Scholar Jim Blackburn. With three months still left in this year’s hurricane season, Blackburn discussed the Houston area’s vulnerability to flooding and storm surges and how rapidly intensifying storms due to climate change may change evacuation plans. Read the Q&A below:

What general environmental and economic risks would the Houston region face today if a Category 4 hurricane like Ida — or a more powerful storm — were to make landfall over Galveston Bay?

Ida is a prime example of a worst-case future for Houston. Ida rapidly intensified from a Category 1 storm to a strong Category 4 storm, meaning that many residents along the Galveston Bay shoreline might not have had time to leave if the same storm had come ashore here. A Category 4 storm surge would be magnified within Galveston Bay and could easily be greater than 20 feet high on its western shoreline, destroying the bayfront housing and flooding the industrial areas of Bayport and the Houston Ship Channel. It is likely that storage tanks containing oil and hazardous materials would rupture, destroying our economic base on Galveston Bay along with most of the development along its shoreline and leading to perhaps the worst environmental disaster in United States history. Across the country, gasoline, diesel and jet fuel supplies would likely be reduced by as much 10% to 15% for several months, and many of these industries would be shut down for months, if not years. It would be a bona fide economic, environmental and social disaster.

What is the status of plans meant to protect the region from storm surges?

At present, two major protection plans are being developed and/or implemented for the Houston region. The “coastal spine” is being developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and is close to internal approval by the Corps and potential authorization for construction. That project will be built along the coast in pieces and will likely not be completed until the mid-to-late 2030s. The Galveston Bay Park Plan is a second line of defense intended to protect the western shore of Galveston Bay and the industrial areas of Bayport and the Houston Ship Channel, and is compatible with the coastal spine. The park plan is awaiting approval of a detailed engineering study by Harris County, the city of Houston and the Port of Houston, and if plans unfold as currently indicated, it could be constructed perhaps as early as 2030.

What are the obstacles to completing such plans?

In many respects, coastal surge protection and flooding rainfall are two separate projects. Much has been done within our region to increase our protection from rainfall flooding, and more is on the way. However, surge flooding, which is rarer than rainfall flooding, is a very different type of problem. Major alternatives to address surge flooding are very expensive, difficult to engineer and potentially have very severe negative environmental impacts. These coastal surge projects involve multiple stakeholders that often have diverging points of view. These are among the most difficult of all of our projects, and that difficulty is magnified by climate change, which is increasing the severity of these storms, often exposing our current methodologies as inadequate for the task before us.

How has climate change altered the risks of hurricanes and tropical storms for coastal communities in Texas (and/or the Houston area)?

Climate change is a key factor regarding the risk of hurricanes. These tropical systems are fueled by the heat of the water, and the temperature of the western Gulf has been steadily increasing over the decades. Hotter air holds more moisture. Although the number of tropical storms and hurricanes may not increase, the severity will, according to numerous forecasts. We will see more Category 4 and 5 storms. We will see rapid intensification, as we did with Harvey, Laura and Ida. And our rainfall projections keep getting higher. Under the statistic relied upon from 2010 to 2017, Harvey’s massive rains were considered to have a recurrence interval of 10,000 or more years. One recent study, however, projects that a rainfall event like Harvey can be expected to recur once every 35 to 70 years, and a recent publication estimated that by 2100, Harvey would be expected to recur about every five years. That is what climate change is doing from a hydrologic perspective.

How should the rapid intensification of storms we have seen recently on the Gulf Coast change our calculations with regard to evacuations?

Rapid intensification is a huge issue. Many people could and likely will die because of rapid intensification. The problem is that in the past, when a Category 1 or even Category 2 storm was coming, many coastal residents saw that they did not need to evacuate. As a result, many of our coastal residents continue to depend upon these past experiences to inform their current decision-making. However, rapid intensification can change a Category 1 storm overnight into a Category 3 or 4 storm. That happened with Laura last year, and luckily for Houston, Laura curved and hit southwest Louisiana instead of us. And we just saw it with Ida. Unfortunately, many people either are unaware of rapid intensification or will simply dismiss it as fearmongering, and they may pay a very high price for such thinking.

In the event that local officials do not have the warning time necessary to issue an evacuation order, what policies or infrastructure should be put into place to protect residents from storm impacts?

Arguably, rapid intensification will make the coastal margins more and more dangerous over time. The coastal spine, when complete, will help, but it is only built to withstand a large Category 2 storm event. It will be overtopped by a Category 4 or 5 storm, which will generate serious damage along Galveston Bay unless the Galveston Bay Park Plan is also completed. Until such protection can be developed, the coastal edge will be at serious risk. It makes sense to consider moving back from the bay margin, as sea-level rise will also become a more urgent issue as we get into the 2030s and beyond. The bottom line is that without massive protection, it may eventually become too dangerous to continue to support development along the gulf and bay shoreline.