By Mark Finley

Fellow in Energy and Global Oil

The 2021 edition of the bp Statistical Review of World Energy was published last week, which means it’s time for my annual commentary. This year’s release is the 70th anniversary edition; as always the Review is a must-read for anyone interested in the world of energy. (Annual disclosure: I led the production of the Review for a dozen years…)

The Review contains comprehensive, objective global data on every energy form as well as key minerals.[1] The focus of bp’s analysis accompanying the Review this year validates the headlines we’ve read over the past year: 2020 saw a sharp decline in global energy demand (-4.5%) and energy-related CO2 emissions (-6.3%). (Though as chief economist Spencer Dale notes, that record decline in CO2 came at the expense of the world economy’s worst contraction since the Great Depression.)

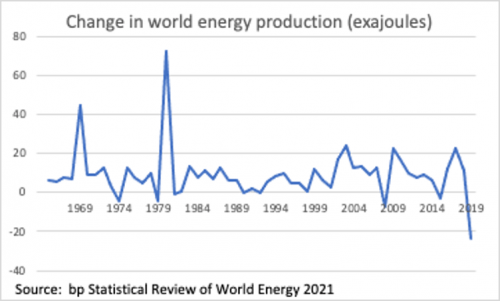

One item that the Review does NOT contain is global energy production; it has data on total energy consumption, and production of every individual form of energy, but it does not aggregate that production data into a total energy production table. As I explained in last year’s commentary, however, a simplifying assumption allows me to build my own total energy production table.[2]

The results are illuminating. As with consumption, global energy production dropped sharply (-4.2%) – the biggest decline (in both absolute terms and in %) in the entire bp data set, which goes back to 1965. Yet global energy production did not fall quite as rapidly as did global demand.

Regional data: US leads the energy production decline

The decline was widespread, with record declines in both OECD (-4.8%) and non-OECD (-3.9%) countries. The US (the world’s 2nd-largest energy producer), saw a decline of 5.3%, the largest decline in the world last year, and the largest domestic decline on record. Production of all fossil fuels, nuclear power, and biofuels all declined.

- According to US Energy Department data, the US had a record decline in terms of the energy content of oil production, but NOT in volumetric units (barrels per day, with the record decline being in 1989); this is a reflection of the changing quality of US oil production – including crude and natural gas liquids – as a result of the shale revolution. (And a useful reminder of the limitations of my “simplifying assumption”! )

- The US also saw a record decline in domestic coal production, as both domestic demand and international markets slumped – more on the latter theme later.

- While natural gas production declined, it did not see a record decline in 2020. My colleague Anna Mikulska and I have written elsewhere about shifting US oil-natural gas production dynamics during the pandemic.

In addition to setting a record domestically, the overall decline in US energy production last year also was the 2nd-largest global energy production decline on record, exceeded only by Saudi Arabia in 1982. In that year, the Kingdom cut oil production by a massive 32% (3.3 Million barrels per day, Mb/d) as OPEC introduced formal oil production quotas for the first time in response to collapsing global demand and rising non-OPEC supply following the oil shocks of the 1970s.

Elsewhere, Russia (the world’s 3rd-largest energy producer) also saw a record production decline (and even larger than the US in percentage terms, -7%).[3] But the world’s largest energy producer, China, actually had the world’s largest increase in domestic energy production last year. While many have noted that China led the world in growth of production in renewable energy last year, it also increased domestic production of oil, natural gas, and coal. Indeed, China had the world’s largest increase in production of natural gas, coal, nuclear power, hydroelectricity, and (non-hydro) renewables – and the 3rd-largest increase in oil production.

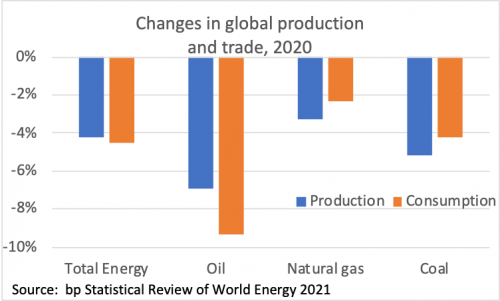

By energy type: Oil hard hit by transport shut-downs

Among energy sources, oil remains the world’s leading fuel source, but it saw by far the biggest global decline last year. Global oil production fell by 6.6 Mb/d – a record both in percentage terms (-6.9%) and volumetric terms. As with total energy, global oil production did not fall as rapidly as did global consumption, even with the “OPEC+” group delivering the largest coordinated production cuts the world has ever seen and with lower prices causing investment and production to collapse in the US and elsewhere. As bp notes, oil stands out – and drives – the global energy story during the pandemic; not only is it the world’s largest energy source (31% of total energy demand last year), oil was disproportionately impacted by COVID-related transportation shut-downs.

Turning back to production, Russia – part of the OPEC+ group – saw the world’s largest decline (-1 Mb/d), with large declines also seen in Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq (in addition to the US).

Both OPEC and non-OPEC countries as groups recorded record declines, with 86% (42 of 49) of countries named in the bp production table seeing lower output. Interestingly, however, among the world’s top-10 producers, only the US (sort of, as discussed above) and the UAE saw record declines last year. As mentioned earlier, the decline in Saudi oil production last year was dwarfed by the experiences of the early 1980s. Among other countries with large declines in 2020, the Russian decline was smaller than the losses seen in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Iraqi (and Kuwaiti) output fell more rapidly in 1991 following former’s invasion of the latter, while Libyan output fell more rapidly during the Arab Spring. It is useful to note that in most cases, domestic unrest or regional conflict – rather than global market developments – have driven record oil production declines among major producers.

Globally, natural gas production also saw a record decline, falling by 3.3%. Yet none of the world’s top ten producers suffered a record decline—rather, the decline of natural gas production was broadly-based, with 40 of the 50 countries named in bp’s production table seeing declining output last year. And as noted above, natural gas – unlike oil and total energy– saw global production decline more rapidly than demand, even without coordinated producer action as we saw with oil.

After oil, global coal production had the largest decline (-5.2%), though unlike oil it was not a record decline – which happened in 2016 when production in China (by far the world’s largest producer) saw a record decline at the same time US output fell sharply. (2016 was the largest US decline on record until last year.) In addition to falling power generation and industrial activity – coal’s main markets – strong increases in generation from renewable energy also hurt global coal demand.

As mentioned earlier, Chinese coal production actually grew last year, and China increased its share of global production to 51%—so where did the global decline come from?

Energy trade fell more rapidly than production

Exporters! In addition to the US, record production declines were also seen in Indonesia, Colombia, Russia and Australia—all significant coal exporters.

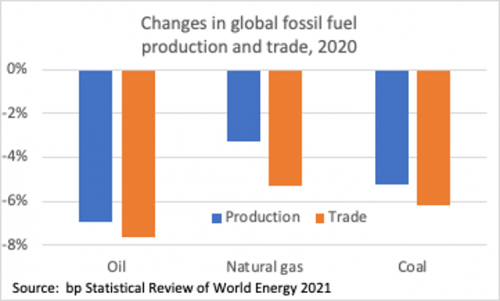

This highlights a fascinating dimension of the global energy story during the pandemic: Trade. Fossil fuels are by far the most widely traded primary energy sources. In addition to being by far the largest sources of global energy use – accounting for 83% of global energy use last year on bp’s data – they are also parts of global markets: nearly three-quarters of world oil production is traded internationally, as is nearly one-quarter of natural gas and 20% of coal.

And on bp’s data, global trade for each of the fossil fuels fell more rapidly than production. (As an aside, WTOand IMF data show that this was also true for all global merchandise trade, which fell by 7.5% last year, more than double the rate of decline in the world economy.)

And by the way, this weakness in global energy trade during the pandemic was not isolated to fossil fuels.

Global nuclear power output also declined last year (-4.1%, well below the record decline of 7.7% in 2011 after the Fukushima accident). But nearly half of the global decline was in one country, France, which did see a record decline of 11.6%. With falling European power requirements (generation fell by 3.3%) and strong growth in generation from renewable sources (+9%), the continent’s need for French electricity exports fell substantially (-7%). With nuclear output accounting for more than two-thirds of French power generation (and renewables growing rapidly), trade drove the country’s record nuclear decline.

It will be interesting to see if global trade (including the energy world) recovers along with the economy and energy demand this year, or whether the weakness in trade heralds a period of more protectionist policies.

So to wrap up: while the world’s has rightly focused on the demand side of the global energy story during the pandemic, there are important stories to be told about supply and trade as well…stories that will have (equally) consequential implications for global CO2 emissions and economic growth.

And that’s just a tiny slice of the information available in the bp data. My advice (admittedly from a true energy nerd): Read it for yourself…crunch the numbers…think…and enjoy!

[1] This year’s edition adds data on methane flaring and wind/solar generation capacity.

[2] According to bp, the reason is the wide variances of energy content of oil production around the world. By assuming oil production for every country has energy content in line with the global average, I can build a global energy production table from the fuel production tables. This is admittedly a rough approximation, but it’s a reasonable coping measure that allows us to draw some useful analytic insights.

[3] bp reports data for Russia and other former Soviet republics from 1985; before that, all were reported in a single USSR line item.

This article originally appeared in the Forbes blog on July 12, 2021.