By Mark Agerton, Ph.D.

Nonresident scholar, Center for Energy Studies, Baker Institute

Ben Gilbert, Ph.D.

Assistant professor of economics and research fellow, Colorado School of Mines’ Payne Institute

Jim Krane, Ph.D.

Wallace S. Wilson Fellow for Energy Studies, Baker Institute

Global CO2 releases have risen by more than 50% since 1992, the year of the U.N.’s first climate summit. Three decades of failure show that stanching CO2 emissions is arguably the toughest collective problem humanity has ever faced.

While taming carbon is crucial, that process shouldn’t delay Americans from choking off emissions of a much more powerful greenhouse gas: methane.

Why focus on methane? First, because methane is extraordinarily bad. Second, because it’s easy to fix, and we can do so unilaterally by establishing a straightforward federal tax.

Methane’s climate impacts come on harder and faster than CO2’s. Over the first 20 years, 1 ton of methane leads to 85 times the warming of CO2. Since CO2 sticks around longer than methane, it’s important to cut CO2, too. But cutting methane today buys time for more difficult CO2 cuts tomorrow.

The energy industry is society’s second-biggest methane emitter after agriculture. And the U.S. energy industry ranks second in the world in emissions — just behind Russia’s. Zeroing out methane from the oil and gas sector is simpler and cheaper than doing so in agriculture and would actually move the needle on climate change.

We think most oil-sector methane emissions would be detected and stopped with a federal tax somewhere north of $1,500 per metric ton in 2021. That’s equal to $29 per thousand cubic feet (mcf). A U.S. Senate bill introduced in March puts the charge at $1,800/ton in 2023.

A lot of U.S. methane emissions occur through oil and natural gas production and transport, so oil and gas companies would be on the hook.

We don’t expect many firms to actually pony up $29 for each mcf of methane they emit. Methane, or natural gas, currently sells for just $3/mcf. Producers facing a tax 10 times greater than the market value of that gas would take action.

Our hope is that energy companies replace leaky valves, stop venting gas from well completions and tank batteries, and make sure that flares stay lit instead of belching methane into the air.

Why $1,500 per ton?

That’s the U.S. government’s estimate of the “social cost” of methane damage. In other words, a ton of methane in the atmosphere traps enough heat to cause $1,500 worth of damage to crops, to worker productivity, to property from floods and wildfires, and to societies when these disasters trigger mass migration. An efficient tax would push these costs onto polluters, rather than society.

By contrast, the social cost of CO2 is just $51 per metric ton.

Some might ask why new methane regulations are necessary. President Biden and Congress just rolled back the Trump administration’s methane deregulation, reverting to the Obama administration’s rules. That’s a good start. The Biden administration has also asked pipeline owners to step up inspections.

But the Obama rules are outdated. They prescribe technology standards for leak detection and repair. These made sense in 2016, before newer remote sensing technologies — satellites and ground-based sensors — could pinpoint emissions. Now we’re better off imposing a tax and letting emitters figure out the most cost-effective way to fix their equipment.

How might the tax be imposed?

Satellite data allows the government to figure out the average emissions rate in a region. The government then taxes oil and gas companies based on the regional average. If companies believe they were cleaner than average — and thus overtaxed — they can certify their actual emissions through a third-party auditor and avoid some or all of the tax.

The proposed Methane Emissions Reduction Act, introduced by Sens. Cory Booker, Brian Schatz and Sheldon Whitehouse, captures many of these suggestions and deserves broad support.

Reducing emissions isn’t free, but that doesn’t mean there’s not a sound business case for doing so. The IEA estimates that half of the global methane abatement opportunities would pay for themselves by increasing natural gas sales volumes.

Plus, emissions certification could catalyze a market for “clean” natural gas that might be sold for a premium to climate-conscious buyers like those in the European Union. This is already happening with Project Canary certifying low-emissions gas.

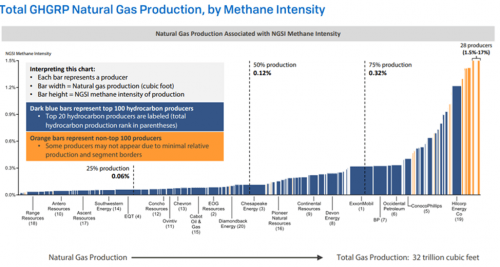

Small producers may protest the costs of upgrades and monitoring. And state regulators have been loath to challenge small producers and get them to pollute less. But small producers cause a disproportionate share of methane emissions. That’s why federal action is key.

Small producers can also share the cost of monitoring emissions. It’s cheap to add a neighbor’s wells to existing satellite or airplane-based monitoring. Revenues from the methane tax might also help. Plugging abandoned wells would also create jobs and further reduce methane emissions.

A steep methane tax might not be popular with oil and gas companies. But if a company is only profitable because society pays for its climate damage, that company shouldn’t be in business.

Figure 1: Small natural gas producers dominate the highest intensity methane emitters in the United States. Note that large producers ExxonMobil, BP, Occidental and Conoco Phillips are also large emitters. (Source: Clean Energy Task Force and Ceres 2021 https://www.catf.us/resource/benchmarking-methane-emissions/) used with permission

This article originally appeared in the Forbes blog on July 12, 2021.