By Joyce Beebe, Ph.D.

Fellow in Public Finance

In late July, Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar delivered a bleak economic outlook for the state’s economy: the amount of general revenue funds available for the current biennium is expected to be $11.5 billion less than originally estimated in October 2019. This massive yet unsurprising reduction, primarily driven by the pandemic and depressed oil prices, pushed Texas’ budget from an estimated $2.9 billion surplus to a $4.6 billion deficit.

Lower infection rates, enhanced economic recovery or additional federal assistance may help narrow the budget shortfall down the road. However, these factors involve high levels of uncertainty and are mostly beyond the control of state officials. Many residents therefore support tapping into Texas’ sizable Economic Stabilization Funds (ESF), commonly known as the “rainy day fund,” to alleviate the state’s economic challenges and to facilitate a stable recovery. This blog post reviews some background of the Texas rainy day fund, recent developments and issues to consider when the state Legislature makes withdrawals.

The Texas ESF Mechanism

The Texas ESF was created through a constitutional amendment in 1988 after falling oil prices caused a statewide recession. The crude oil and natural gas production taxes (severance taxes) are the major funding sources of the ESF, and the current funding mechanism was established in 2015. Prior to 2015, the ESF received 75% of each year’s oil and natural gas severance taxes in excess of fiscal 1987 amounts (i.e., $531.9 million for oil and $599.8 million for gas). During the ESF’s early years, it never accumulated a significant balance. However, the fund began to grow rapidly in size around 2000 as a result of increasing oil prices and subsequent prosperity in the oil industry. Since 2007, the ESF balance has consistently exceeded the billion dollar mark despite several major withdrawals. In late 2014, lawmakers passed a constitutional amendment that reduced the revenue going into the ESF. Specifically, this amendment diverted half of the severance tax revenue previously designated for the ESF to the State Highway Fund to address the expansion and maintenance needs of the state highway system.

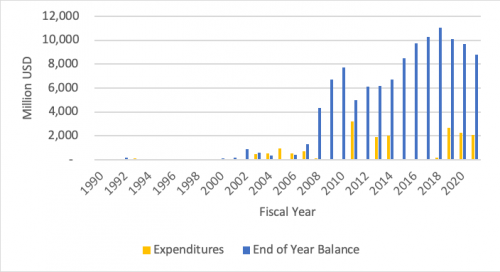

In terms of the use of funds, lawmakers are allowed to use the ESF for three primary purposes: to address a budget deficit during a biennium, to respond to a projected decline of revenue in the following biennium or to make withdrawals for any general purpose. Appropriations authorized under the first two conditions require approval by three-fifths (60%) of the legislature. The third type of spending, which is less restrictive in nature, requires a two-thirds majority (67%) to authorize the appropriation. Figure 1 summarizes ESF balances and withdrawals.

Figure 1: ESF Balances and Withdrawals

Data sources: (1) for fiscal years 1990 to 2019 actuals – Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Fiscal Management – ESF History Table; (2) for fiscal years 2020 and 2021 estimates – Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Certification Revenue Estimate (revised July 2020). (Appropriations authorized by a certain legislative session may spread across multiple fiscal years.)

Recent Developments

Prior to the pandemic, most ESF-related discussion centered around whether Texans have been saving too much in the rainy day fund and what portion of the fund balance should be invested in higher yield instruments to preserve its value. For instance, the ESF is required to maintain a sufficient fund balance in response to the liquidity needs. Until 2019 (discussed below), the sufficient fund balance had been decided by a joint select legislative committee prior to each regular legislative session. For the 2020-21 biennium, this amount was set at $7.5 billion. Traditionally, the sufficient fund balance has been invested in short-term, low-risk and highly liquid investments, such as Treasury instruments. However, because of the persistent low interest rate environment, the need to balance risk (higher yield) and return (value preservation) intensified. As such, the Legislature introduced the “prudent investor standard” in 2015, which essentially allowed the amount above the sufficient fund balance to be invested in fewer liquid and higher-yield instruments to maintain purchasing power.

In 2019, Senate Bill 69 (SB 69) further allowed a higher portion to be invested out of Treasury instruments beginning in fiscal 2022. The bill requires at least 25% of the ESF balance to be invested in a manner that ensures liquidity, but the comptroller can invest assets above this portion in higher return instruments that are consistent with the prudent investor standard. This bill also sets the sufficient fund balance at 7% of general revenue-related appropriation made for that fiscal biennium, discontinuing the practice of having a joint legislative committee decide the amount.

As a result of the accumulating ESF balance, there has been pressure to spend down the ESF in recent years. Between the fund’s inception and the 85th legislature in 2017, the ESF has been primarily used to cover budget deficits, public education, infrastructure, disaster relief, health and human services, corrections, economic development initiatives and grants to local entities. During the 86th legislative session in 2019, lawmakers authorized the largest ESF withdrawal in the fund’s history. The $6.2 billion ESF withdrawal, described in supplemental appropriation Senate Bill 500 (SB 500), includes funds for Hurricane Harvey recovery-related expenses, the Medicaid shortfall, pension liabilities for the Texas Teacher Retirement System and improving state hospital facilities, among numerous other appropriations.

The pandemic changed ESF-related discussion completely. The concern is no longer whether Texans are saving too much; instead, many urge lawmakers to start using the ESF and alleviate the economic and social damage caused by the pandemic, especially now that other states have started to do so.

Most states have some form of rainy day fund, although the fund balances, contribution mechanisms, authorized use and revenue sources vary greatly. So far, roughly a third of states either made or authorized rainy day fund withdrawals. These states used their funds to close current budget shortfalls, cover coronavirus-related expenses, meet budgetary needs for the coming fiscal year or for a combination of purposes. There has also been a wide span of withdrawal amounts, ranging from some states using a small portion of the fund balances to others completely emptying their accounts. For instance, Nevada and New Jersey have used up all their rainy day savings. Rhode Island, Alaska and California exhausted about half of their fund balances. In comparison, Arizona and Georgia have spent a relatively minor portion on coronavirus-related expenses, but more appropriations may be pending.

Considerations for ESF Withdrawal

The comptroller’s office estimates that at the end of the current biennium in August 2021, Texas’ ESF will have an $8.8 billion balance. Texas has refrained from drawing down the ESF over the last few months, potentially because many federal relief programs were still in place and their effects were still unfolding. In addition, it requires the governor to call a special legislative session for lawmakers to authorize the withdrawal. With the funds from several federal assistance programs already run out or getting low, crucial issues in the coming 87th Texas legislative session will be how best to use the ESF and how much to spend. Many have anticipated that, similar to other states, the ESF will be used to balance the current budget, meet increased health care needs, maintain pandemic safety in schools and cover additional expenses related to the coronavirus.

Although ensuring public safety and facilitating stable economic recovery remain the most important objectives, the following experiences from prior years and other states may help lawmakers make ESF spending decisions.

First, recent volatility in oil prices and reduced demand will lead to lower severance tax collections. As a result, the funds will take longer to be replaced and not be replenished as quickly as with prior withdrawals. The ESF and the State Highway Fund both receive transfers from oil and natural gas severance taxes collected during the previous fiscal year. For fiscal year 2020, the comptroller’s office expects both the ESF and the State Highway Fund to receive $1.7 billion in transfers from the General Revenue Fund for severance taxes collected in 2019. For fiscal year 2021, the estimates show that each fund will receive $1.1 billion for severance taxes collected in 2020. The comptroller estimates the severance tax collection will drop significantly in 2021, and the transfer to each fund in fiscal year 2022 will be $620 million, a 45% reduction from the $1.1 billion amount in fiscal year 2021.

Second, some evidence shows that although the state credit rating depends on many qualitative and quantitative factors, a low balance in a state’s rainy day fund could lead to credit rating downgrades. Because of the increasing volatility of state revenue streams in recent years, a sizable rainy day fund provides extra cushion to offset budget shortfalls and is viewed favorably when considering a state’s financial strength.

The consequence of a lower state credit rating is a higher cost of borrowing by the state. When states sell bonds to finance construction and infrastructure projects (such as roads, airports or parks), all else being equal, lower credit ratings generally imply higher repayment risks. This means states need to pay higher interest rates to attract investors. In addition, states may also borrow from the public to repay their higher interest loans from the federal government, such as the Title XII loans that finance their unemployment insurance benefits. A weak credit rating means that this arbitrage strategy will not generate any economic benefit for the state.

However, other observers indicate that simply drawing down the rainy day fund balance does not mean states’ creditworthiness is immediately impaired. After all, the ESF is designed to be used during economic downturns or in response to “rainy days.” Studies have shown that the structural elements of rainy day funds, including whether policymakers are disciplined about spending and replenishing the funds, are equally important in affecting the credit ratings. In addition, rating agencies also review whether or not states take budget-cutting actions in response to the decline in revenue when making credit rating decisions.

Texas lawmakers have a solid starting point when it comes to credit rating considerations: besides a sizeable ESF balance, Texas’s general obligation debt currently has the highest credit rating from rating agencies. In a report published a few years prior to the pandemic, rating agency analysts indicate that among the four most populous states (California, Texas, Florida and New York), Texas has rich natural resources, and policymakers are experienced with factoring in oil price fluctuations in state revenue and budget management. As such, the report concludes that among the four states compared, Texas is the most prepared for a recession.

Finally, some observers argue that the ESF should not be used to pay for recurring expenses. From a fiscal discipline perspective, recurring expenses should be funded out of general revenue, whereas ESF usage should be limited to extraordinary expenditures such as for national disasters or economic recession. They caution that consistent use of the ESF to cover state budget shortfalls may lead state lawmakers to be overly dependent on the savings and not disciplined enough to balance budgets. During the current recession, the line between whether the ESF is being authorized to cover recurring expenses or pandemic-inflicted economic damage will be especially blurry; however, states do need to consider whether structural reforms to their tax systems are necessary in the long term.