By Benigna Cortés Leiss

Nonresident Fellow in Latin American Energy

Center for Energy Studies

and

Adrian Duhalt, Ph.D.

Postdoctoral Fellow in Mexico Energy Studies

Center for the United States and Mexico and Center for Energy Studies

The oil glut and the unprecedented drop in demand with plummeting oil prices due to the coronavirus pandemic is revealing the strengths and weaknesses of oil firms globally. Hence, we often find ourselves consumed with the stock performance and capital expenditure projections of international oil companies (IOCs): the ExxonMobil’s, BPs and Chevrons of the world. Meanwhile, more than 80 percent of global reserves is in the hands of the National Oil Companies (NOCs). While these NOCs are somewhat similar in terms of their ownership structures or reliance on upstream activities, their resilience and preparedness to supply and demand shocks varies from one case to another. Here we look at four distinct NOCs: Ecopetrol, Petrobras, Petronas and Pemex and consider the current crisis through lenses that reflect the specific realities of each company. As different as these realities and responses are, our analysis points to special distinctives exhibited by the Pemex’ strategy under AMLO administration.

As expected, firms with the strongest balance sheets and flexible portfolios to manage their production and cost structures are better prepared to weather market uncertainty. In times of crisis, business flexibility and diversification pay off. But this is a principle not every oil company is eager to embrace. And this is especially true among NOCs that are prone to be hostage of political and policy swings at home. The ability to successfully manage this (and any) crisis is also a function of the respective governments’ ability/willingness to provide fiscal relief and or capital injections and the governments’ and companies’ disposition to cut production, capital expenditures and/or delay project development and/or access the market for debt.

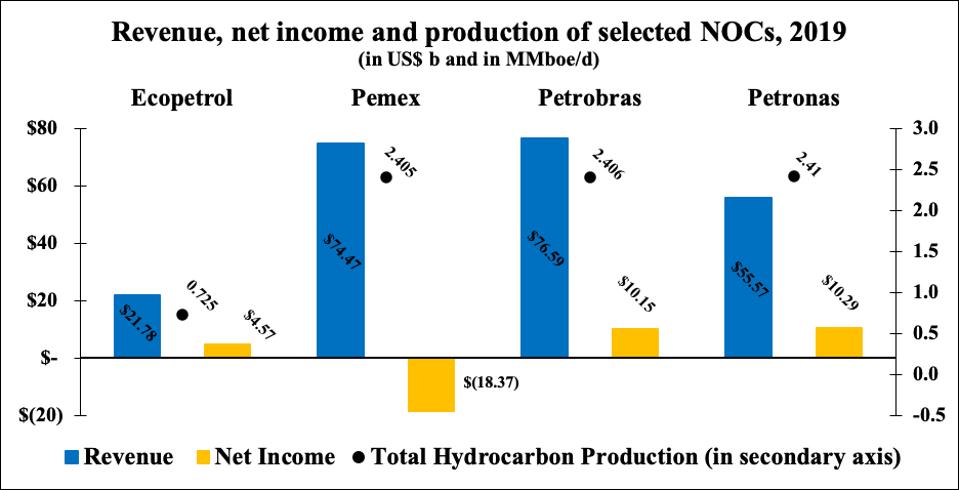

Revenue, net income and production

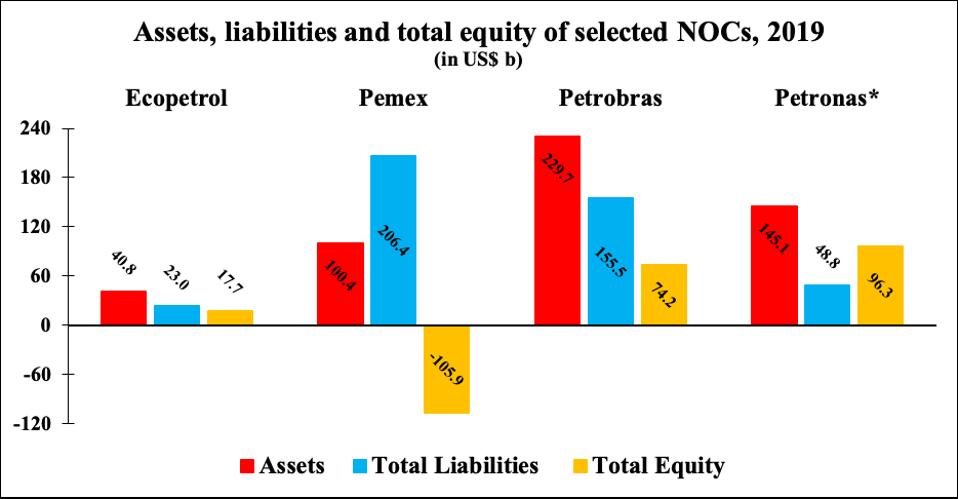

And with NOCs’ balance sheets taking a toll from low oil prices, although going into the crisis, there was a wide variation in credit worthiness reflecting good or bad management and politics, credit rating agencies are watching closely. Borrowing costs are on the up for Pemex, whose credit worthiness has been sent by Fitch (BB-) and Moody’s (Ba2) to speculative/junk territory. Petrobras rating by Moody is Ba2, stable. Ecopetrol has maintained investment grade status despite recent downgrades by Fitch (BBB-). Petronas, on the other hand has had its rating affirmed by Moody as A2 while Fitch revised its rating to A -.

Assets, liabilities, total equity

But let’s step back and take a closer look at the four companies and how they have dealt so far with the current crisis.

Ecopetrol, the Colombian national oil company which is owned by the Nation (88.49%) and private investors (11.51%), has announced deeper cuts to its 2020 capital expenditures. In March, the firm revealed that investment will amount to between US$3.3 Bn and US$4.3 Bn, down from an pre-crisis range of US$ 4.5 Bn and US$ 5.5 Bn. But more recently, said figure has been put at between US$2.5 Bn and US$3 Bn. As a result, the production target for 2020 has also been revised downward by 50,000b/d to 710,000 boe/d. On these counts, Ecopetrol does not differ that much from IOCs.

Brazil’s Petrobras, is a fully integrated company controlled by the Brazilian state that allowed private participation in the upstream business following the energy reform in 1995 and] issued shares that are currently traded in the New York Stock Market. It ended 2019 with a market capitalization of $101Bn, and has become a world leader in deep and ultra-deepwater exploration and production. To focus on upstream, it is going through divesting some of its non-core business like retail and distribution that took place in 2019 as well as local distribution companies it owns, and the gas pipelines as well as 6 of its 13 refineries, among others. It sold a previously acquired refinery in Pasadena, Texas with capacity to process about 110,000 b/d for $350 million. It will be interesting to see if this move away from diversification in the downstream turns out to be a positive in the post-coronavirus oil market.

To face this crisis, the company announced a production cut of 200 to 300 Mb/d. They also have indicated that will access one of their credit lines to meet their cash flow needs and postpone their divestiture plans given the current market conditions.

Petronas is the Malaysian national oil company, 100% state owned founded in 1974. However, it has a different profile to the other three NOOCs with three distinct segments that include international and private participation. Upstream with oil and natural gas exploration and production, in the domestic and international markets, with natural gas represent more than 50% of its total production. It is a leading significant natural gas producer and it has become a major LNG player.

Through its international E&P subsidiary Carigali, it participates in opportunities around the world. For example, Carigali, participated as partner of Repsol in Mexico’s bid rounds for two exploration blocks where they have recently made two deepwater discoveries in Mexico’s Gulf of Mexico.

Petronas business also comprise midstream and downstream activities including refining, liquefaction and regasification plants, as well as LNG shipping and trading. Japan, South Korea, China, and Taiwan are among the major LNG customers.

To face the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak, Petronas has announced that it will be striving to minimize the impact to its planned domestic Capex program. Still they expect that some upstream projects will be delayed due to the prolonged lockdowns implemented in the country and further disruptions to the global supply chain. Also, it appears that the economic activity may start an incipient recovery in Asia potentially having a positive impact on the demand of oil and gas.

Malaysia has agreed to cut production by 136,000 barrels per day (bpd) as part of the 9.7 million bpd supply cut by Opec+. The Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries is using October 2018 numbers as the baseline. On that note, Malaysia’s cut is about 20% of its estimated 2018 production of slightly above 680,000 bpd.”

Other majors such as Chevron, Shell and Norway’s Equinor have announced 20% capex cuts. That said, Petronas is on a much better footing in terms of balance sheet position. At end-2019, Petronas was sitting on cash of RM123 billion against RM55 billion in total debt — a rare ratio among oil majors. In its latest statement, Petronas says it will strengthen its mitigation strategies towards cushioning the short, medium and long-term impact of Covid-19 on its business.

Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) whose oil production peaked in 2004 at 3.4 MMb/d, has seldom benefited from the periods of high oil prices. Instead of building cash reserves in order to fund its capex and operations, the government taxed Pemex to finance public spending and made the company rely on debt financing. Pemex is now the most indebted oil company in the world.

Last year, despite having revenues of $74.5 Bn., inefficiencies and liabilities resulted in Pemex posting a loss of $18.4Bn. President López Obrador seems to underestimate that these inefficiencies and liabilities, if left unchecked, may lead to even greater losses in 2020. Every barrel of oil processed at Pemex’ own refineries during 1Q2020 reported a loss of $12.51. For AMLO, part of the near-term solution to falling oil demand is to increase the utilization rate of refineries, a decision that will inevitably result in higher yields of low value products such as fuel oil and hence losses. Nor has the dire economic situation for PEMEX reduced AMLO’s plan to build a new refinery that will cost more than $8 billion. Expand on AMLO’s unwillingness to cut production by more than 100kbd in OPEC discussions and no indication that shut-in of production is likely. President Lopez Obrador has been reluctant to reduce capex levels until recently when Pemex announced a cut of 23 percent to its pre-crisis upstream investment, which in dollar terms represents a more timid/smaller cut than that of Ecopetrol.

Thus, it appears that from these four NOC’s, Pemex seems to be taking a much laxer approach in comparison to what its piers are doing regarding reducing production and/or capital expenditures. Petrobras, on the other hand, has announced plans to trim their production and expenditures as well as accessing the capital markets. Ecopetrol also plans to decrease production and cut its capital expenditure as well as having fiscal relief from the government. Petronas seems to be facing the crisis with minor adjustments in capex, although it has agreed to production cuts as part of the OPEC+ agreement, and with the best credit rating among the four companies. Its diversification into LNG might be helpful as well.

In summary, PEMEX seems to be underestimating the complexity and depth of today’s price and demand critical environment while the other three companies are taking steps reflecting the new oil price and demand environment.

Benigna Cortés Leiss is nonresident Fellow in Latin American Energy at Rice University’s Baker Institute and the former general director of Chevron Energía de México.

Adrian Duhalt is the postdoctoral fellow in Mexico energy studies for the Center for the United States and Mexico and Center for Energy Studies at the Rice University’s Baker Institute. He is also an associate professor at Universidad de las Américas Puebla (UDLAP).

This post originally appeared in the Forbes blog on May 20, 2020.