By Jorge Barro, Ph.D.

Fellow, Public Finance

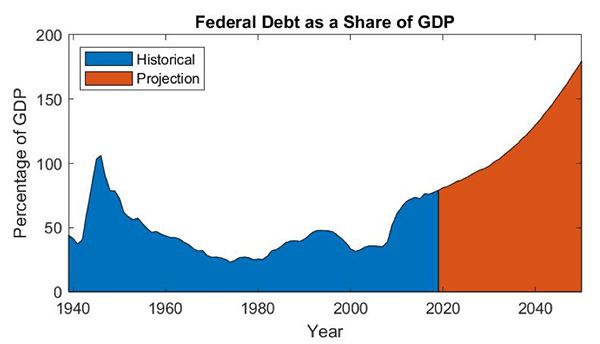

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently released its long-term U.S. government debt projection, and the outlook is cause for concern. The 30 year debt projection was revised upward from 144% of GDP to 180% of GDP. The good news is that economy shows no signs of strain from this unsustainable debt path. The bad news is that the executive and legislative branches also show no signs of willingness to work together to resolve the budget problem. This political gridlock leaves many questions regarding how an impending debt crisis might play out over the foreseeable future.

Figure 1.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and U.S. Office of Management and Budget (historical); Congressional Budget Office (projection)

For years, Americans have been warned about the dangerous macroeconomic consequences of rising debt. Standard economic theory predicts that government debt issuance crowds out private investment, driving up interest rates and weakening the economy. Nevertheless, U.S. federal debt has risen to levels not seen since the aftermath of World War II. Meanwhile, interest rates have steadily declined, and the economy continues on its longest expansion on record.[i] With debt expected to continue soaring over the next 30 years, many are beginning to wonder how large debt can grow before it reaches a breaking point.

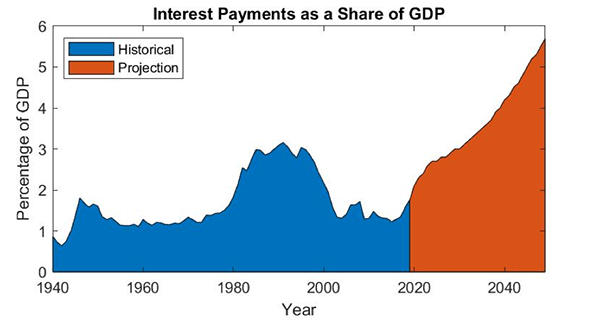

Two possible outcomes could trigger a fiscal response to rising debt levels. The first possible outcome is an economic contraction caused by rising debt. In a recent issue brief, I explained that a demographics-driven increase in savings likely caused interest rates to decline over the last few decades — a trend unlikely to reverse course under current demographic projections. Consequently, the risk of an economic contraction caused by rising debt also remains low in the near term. The second possible — and more likely outcome is an intolerable surge in debt servicing costs. Although interest rates will likely remain low, projected debt levels are expected to grow total interest payments as a share of GDP. Sufficiently high increases in these debt servicing costs will eventually cause Americans to reevaluate their fiscal priorities.

Figure 2.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and U.S. Office of Management and Budget (historical); Congressional Budget Office (projection) [2]

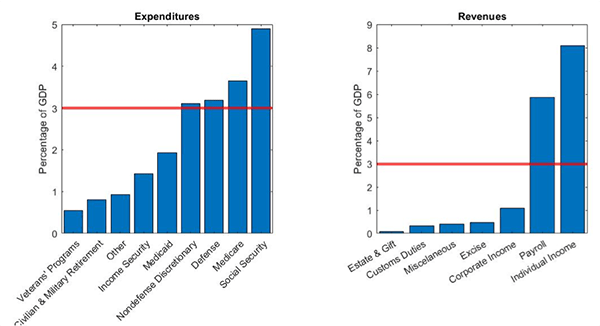

While 3% of GDP may not sound extravagant, such high payments would be enough to finance the entirety of several government programs and a large portion of several others. The figure below shows that interest payments of 3% of GDP could, for example, alternatively pay for all of Medicaid or nearly the entire defense budget. That amount would also pay for most of Medicare or nearly half of the entire Social Security program. In terms of revenues, avoiding those interest payments would be enough to eliminate corporate income taxes, eliminate the employee portion of payroll taxes, or reduce individual income taxes by 37%. Conversely, if nothing is done, these heightened interest payments will prioritize past deficits over other spending programs or tax cuts of the same magnitude.

Figure 3.

According to this historical reference and current CBO projections, policymakers have about 10 years to resolve federal debt growth. By 2030, interest payments are expected to approach the same critical level that existed in 1990 when the president and Congress worked together to resolve the rising debt costs of that era. Policymakers might continue ignoring debt growth for now, but the political risk of making a campaign promise to reject higher taxes or expenditure cuts will steadily rise until this debt problem is resolved.

[1] See https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/07/02/americas-economic-expansion-is-now-the-longest-on-record.

[2] The January 2020 long-term budget outlook released by the CBO only included annual data for debt as a share of GDP. Annual data for interest payments as a share of GDP are from the CBO’s June 2019 long-term budget outlook.