Nonresident Fellow, Energy Studies

On July 31, the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee advanced a bill that would impose sanctions on the Nord Stream 2 (NS2) pipeline, which is currently under construction and could bring up to 55 billion cubic meters of Russian natural gas directly to Germany. The previous month, in June, the House of Representatives’ Foreign Affairs Committee approved a companion bill. The rationale for the sanctions (beyond U.S. retribution for Russian meddling in the U.S. elections): European energy security concerns and protecting Ukraine’s stability.

There is still a considerable way to go for the bill to become a law. After it passes the full Senate, the House and Senate versions need to be reconciled and signed by the president. Thus, it may be a good idea to consider the potential effects of the proposed sanctions.

NS2 would allow Gazprom — the Russian natural gas company that has a monopoly on Russian natural gas pipeline exports — to circumvent the traditional transit route via Ukraine. The pipeline has been one of the most — if not the most — disputed natural gas projects in recent European history. There is a distinct rift within the EU regarding whether the pipeline is an exclusively market-oriented project (the perspective of much of Western Europe) or is designed to expand Russia’s dominance as Europe’s natural gas supplier and could be used to serve geopolitical goals (the perspective of most of Central and Eastern Europe [CEE]). After all, Russia has been known for using its dominant position to exert influence over the CEE.

If imposed, U.S. sanctions would be welcomed by many of the CEE countries. But it is unlikely that sanctions would stop NS2 from being completed. That being said, this tactic could delay construction, make the pipeline more costly and, as a result, diminish the rents that the Russian regime could pocket from gas sales to Europe.

However, since the effect of U.S. sanctions on NS2 would in practice be much more limited than originally intended, the disadvantages could outweigh the benefits.

Sanctions could:

1) Strain existing U.S./Western Europe relationships. While CEE countries would be thrilled to have U.S. sanctions imposed on NS2, their Western counterparts would be much less pleased. In particular, the sanctions could deepen the rift between the U.S. and countries involved in the NS2 project, including Germany, France, Italy, Austria, Netherland or Switzerland.

2) Divide the EU. The sanctions could further deepen the differences between the EU countries on the pipeline and potentially insert more distrust in sometimes-difficult relations between Europe’s East and West.

3) Prove inopportune. Disagreements with some of U.S. European allies may be counterproductive at the time when the U.S. a) is engaged in a trade war with China; b) has imposed sanctions on Venezuela and Iran; c) faces immigration issues on its Southern border and has threatened sanctions against Mexico if it does not help curb the crisis; and d) has been involved in difficult trade renegotiations with Canada and Mexico.

In the meantime, it is unlikely that Russia will cancel the project — if for no other reason than the sheer desire to show its resolve. In the words of former White House Communications Director Anthony Scaramucci: “the sanctions had in some ways an opposite effect because of Russian culture. I think the Russians would eat snow if they had to survive.”

Yes, imposing sanctions would be very well received in Central and Eastern Europe. But strategically speaking, the lack of sanctions, while disappointing, would not make countries like Poland or Lithuania any less committed to the U.S. alliance. Meanwhile, sanctions could make the already strained relationship between U.S. and its Western European allies such as Germany or France even more challenging.

More importantly, the U.S. does not need sanctions to make Russian gas sales to Europe less profitable. Thanks to the increasing LNG exports and a deepening natural gas market, Gazprom will be unlikely to continue its position of dominance in Europe. As long as alternative supplies can access the European market, they will provide a “credible threat” and a price ceiling for Russian gas.

The crucial element is access that includes both sufficient infrastructure and markets open to competition. And it is here where the U.S. can make the biggest impact.

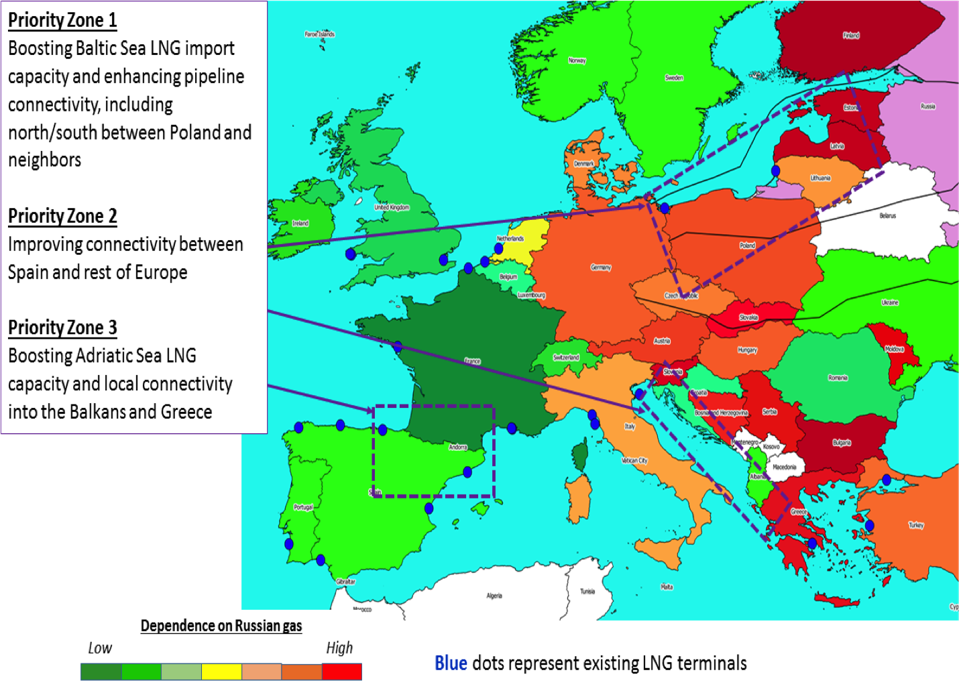

As explained in detail in our 2018 report, the U.S. could directly engage in developing LNG and pipeline infrastructure in those parts of Europe where diversification of supplies is needed. We have identified several areas, including Central and Eastern Europe, where prompt U.S. assistance could make Russia just another normal supplier (Figure 1). We are not talking about formal assurances of government support for U.S. companies to deliver U.S. LNG. Since U.S. companies and not the U.S. government make ultimate decisions on how and with whom to trade, governmental declarations — even those coming from the highest echelons of power — are only what they sound like: declarations.

Figure 1. Priority Zones for Geoeconomic Gas Investment

Priority Zones for Geoeconomic Gas Investment

Instead, we suggest substantive U.S. action that could involve — but are not necessarily limited to — options such as “forgivable loans,” direct financing, project finance loans or assured payback. Importantly, U.S. involvement would be conditioned on the liberalization of European markets to attract more competitors and, in effect, assure possibly the lowest gas prices in Europe.

In the case of Central and Eastern Europe, U.S. assistance could help expand the capabilities of the new LNG import terminals in Poland and Lithuania, speed up pipeline projects such the Baltic Pipe, The Gas Interconnector Poland-Lithuania (GIPL) and the Balticconnector pipeline, or develop new projects altogether. The provision of market liberalization could also facilitate common market projects and balancr areas such as those proposed in 2016 by Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Finland.

Given that many long-term contracts with Gazprom are slated to expire in the 2020s, rapid infrastructure development and market liberalization would ensure a much better bargaining position and remove the geopolitical dimension from the natural gas trade with Russia for those EU countries that decide to continue to buy Russian gas. A similar push could also have great results when applied to Eastern Mediterranean and Spain (dee Figure 1 above).

This leaves the issue of Ukraine. If NS2 is built, Ukraine stands to lose revenues that it has derived for decades from the transit of Russian gas to Europe. However, NS2 would not have an impact on Ukrainian natural gas supplies if we believe in the country’s pledge to completely wean itself off Russian gas. In addition, Europe’s demand for gas exports is projected to grow and if Russia wants to share in this growth it will need more than a replacement for Ukraine’s transit. As a result, the pipeline may be used long into the future. The same goes for unexpected spikes in gas demand during a particularly cold winter, for example. In this case, the Ukrainian pipeline could provide the flexibility that Russia needs as well as the transit revenues that Ukraine craves. There is also the possibility that other Russian gas companies press the government for dismantling Gazprom’s monopoly over pipeline exports and try to use the pipeline. Rosneft has been eying this option for a while now. That said, if Ukraine wishes to extract rents from transit and secure below-market parity prices, it is likely to face a pushback from any gas supplier.

So far, transit fees have not saved Ukraine from economic and political dysfunction. And distinctly anti-market policies geared toward protecting Ukraine’s transit country status may actually support an uncompetitive and inefficient market structure and keep the country reliant on Russia. Ukraine needs to reform the way it operates. It made important steps by recently introducing energy reforms to make its laws compatible with EU standards. Now it remains to be seen how Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s newly elected president and his party, Servant of the People — which just won the majority in the Ukrainian parliament — will implement these laws.

In all likelihood, as the lowest cost supplier, Russia will remain Europe’s main source of natural gas. But Gazprom will have to function within a much more competitive market, and will feel the pressure from other Russian companies. Availability of LNG (from the U.S. and elsewhere) and policy can restrain the company’s inframarginal rents. As explained above, the U.S. could become an important force behind these changes, facilitating diversification, integration, and liberalization of the European natural gas market. Such engagement could be less controversial, less divisive, and likely more productive than sanctions that affect not only Gazprom/Russia but also some U.S. allies.

This post originally appeared in the Forbes blog on Aug. 15, 2019.