In light of the radical changes in the Middle East and North Africa following the Arab Spring, civil unrest has become an issue of utmost concern for policymakers, analysts and academics. Nowhere can the implications of ignored or improperly addressed public discontent be seen more clearly than in Syria’s brutal and potentially regionally destabilizing civil war. Widespread protests are also disrupting — and even overturning — the status quo in Brazil, Turkey and Egypt. In the fourth of a seven-part Baker Institute Viewpoints series, we evaluate the impact that this new wave of civil unrest will have on international politics. In the coming days, institute experts will address the effects on U.S. foreign policy, unexpectedly stable regimes, analytical tools for understanding civil unrest and political philosophical conceptions of “just” societies.

In light of the radical changes in the Middle East and North Africa following the Arab Spring, civil unrest has become an issue of utmost concern for policymakers, analysts and academics. Nowhere can the implications of ignored or improperly addressed public discontent be seen more clearly than in Syria’s brutal and potentially regionally destabilizing civil war. Widespread protests are also disrupting — and even overturning — the status quo in Brazil, Turkey and Egypt. In the fourth of a seven-part Baker Institute Viewpoints series, we evaluate the impact that this new wave of civil unrest will have on international politics. In the coming days, institute experts will address the effects on U.S. foreign policy, unexpectedly stable regimes, analytical tools for understanding civil unrest and political philosophical conceptions of “just” societies.

Read other posts in this series:

- Turkey, Brazil and Egypt: The stakes for the United States by Joe Barnes, Bonner Means Baker Fellow

- Egypt and the Gulf: The illusion of stability?, by Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, fellow for Kuwait

- Chaos in the streets? Blame cyberspace! by Chris Bronk, fellow in information technology policy

- Civil unrest: Is Mexico next? by Tony Payan, fellow in Mexico studies

- A new wave of democracy in Turkey by Dina Shahrokhi, research associate for the Middle East

- Egypt after the coup: Only the beginning of the beginning by Albert B. Wolf, doctoral candidate at the University of California, Irvine

It’s about good governance

No one saw Brazil’s protests coming — not even those who organized them. The protests erupted approximately three weeks ago over the announced hike in bus fares and rapidly spread across the country. The protesters had many grievances, including poor health care and access to public services, and they included both the middle and lower classes — two groups that were supposed to have benefited from rising standards of living in recent years.

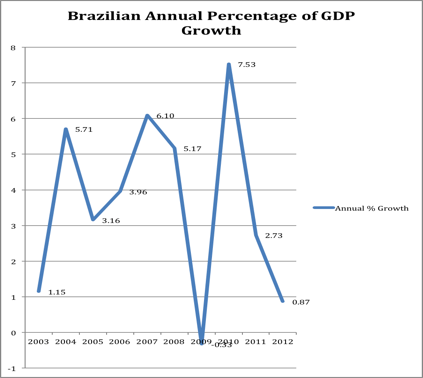

Brazil had prided itself on having the best elites in Latin America, strong rates of economic growth over the last decade and a strong public sector that allowed the government to mitigate unemployment and stabilize its transition to a fully developed nation. But as the chart below demonstrates, Brazil’s economy has been subject to wild swings in economic growth, which may in part be contributing to current unrest.

In addition to wild GDP growth swings, inflation has been a significant problem in Brazil.

Precipitants and preconditions

As a BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) economy, Brazil was considered a strong and stable emerging market. And yet a closer look reveals what Harry Eckstein identified in his seminal article “On the Etiology of Internal Wars” as the preconditions for internal war. The catalyst was the hike in bus fares. That was the spark, but what was the tinder? As Eckstein argues, it is nearly impossible to foretell the “precipitants,” or the factors that will react to give rise to a conflict; thus, we should look at the underlying structural features of civil conflicts — the “preconditions” — if we hope to have any modicum of predictive capacity. And if we look at those in Brazil, we see that the conditions are ripe for civil conflict and long have been.

One of the obvious preconditions in Brazil is economic and social inequality. In a society where the wealthy travel across major cities using helicopters as taxis, there are bound to be those who feel deprived. This sense of relative deprivation can be exacerbated by globalization. Relative deprivation can be distinguished from absolute poverty or deprivation in that people protest or rebel when they subjectively perceive they are deprived. This could be from comparing themselves to others or because of unmet expectations — for example, due to unfulfilled government promises. One of the great frustrations with Brazil’s government is that it is spending millions hosting major events such as the Olympics and World Cup instead of addressing the mundane issues of health care, education and bus fares. A related issue has been the opaque privatization of many of these social services, which benefits the wealthy and those connected to the government but is costly for the poor.

Mass media and protest

As communications technologies proliferate via the Internet and other forms of mass media, people’s expectations rise. They see the lives of affluent Americans in Hollywood movies and compare them to their own. Worse than seeing affluent Hollywood actors, however, would be to see the super wealthy of Brazil and other Latin American states.

The government response

In a strange twist, it is the moderate-left government of Dilma Rousseff that has suffered these protests. If ever there was a party that was supposed to represent the interests of the worst off, it should have been this one. And yet, this administration has come to be viewed as the establishment and has failed to provide the services the middle and lower classes pay for through taxes. Rousseff has responded by suspending bus-fare hikes, as well as by proposing a five-point plan that includes a referendum on campaign finance reform and other political reforms. Her government is also trying to sweeten the contracts on highways and trains in an attempt to respond to protester grievances. The goal is to increase competition to improve the quality of the projects. Rousseff also hopes to use the country’s newfound oil reserves to fund public services, but has hit stiff resistance from governors who need the funds for their coffers.

Conclusions

Only time will tell if Rousseff’s response will appease protesters. But the global character of recent protests — the Arab Spring, protests in Turkey, and protests that spurred the Egyptian military to overthrow a democratically elected government — demonstrates that protest as a form of social action is becoming increasingly popular and effective. Mass and social media may have a lot to do with the rapid spread of these forms of protest.

The underlying grievances of movements across the globe have much in common. They revolve around notions of good governance and the expectation that the state will use tax revenues efficiently for social services. It is not a repudiation of the neoliberal economic model of small states and big markets, but rather an argument that you can have big markets and small states if they efficiently provide public services. In other words, leaders must use increased tax revenues from globalization to make the worst off in society better off — or face the consequences.

It’s as if the whole world started reading John Rawls’ “Theory of Justice,” which is based on a simple thought experiment: Imagine you know nothing about yourself. What kind of society would you design? Rawls makes a persuasive argument that an individual would create a society that works to maximize the position of the worst off. This would not prevent the acquisition of wealth, provided an argument is made that wealth accumulation also benefits the worst off — for example, through the creation of jobs. Brazil’s failures in health care and bus fares — just a few of the protesters’ cited grievances — are viewed as failures to live up to this premise. Like most policy debates, this is not an argument about the role of states versus markets, but one about the expectations of states from democratic, free-market societies.

Nathan Jones is the Alfred C. Glassell III Postdoctoral Fellow in Drug Policy at the Baker Institute. His areas of interest include U.S.-Mexico security issues, illicit networks and cross-border flows. Follow him on Twitter at @natejudejones.

Nathan Jones is the Alfred C. Glassell III Postdoctoral Fellow in Drug Policy at the Baker Institute. His areas of interest include U.S.-Mexico security issues, illicit networks and cross-border flows. Follow him on Twitter at @natejudejones.