By Jacob Koelsch

Student Research Assistant, Center for Energy Studies

Michelle Michot Foss, Ph.D.

Fellow in Energy, Minerals & Materials, Center for Energy Studies

Gabriel Collins, J.D.

Baker Botts Fellow in Energy & Environmental Regulatory Affairs, Center for Energy Studies

Steven W. Lewis, Ph.D.

C.V. Starr Transnational China Fellow, Baker Institute

If China’s dominance of rare earth element supplies is the global energy transition’s “elephant in the room”, then copper is the 800-pound gorilla. China’s push for outbound investment, with attendant strategic nuances, are a hallmark of emerging concerns about raw materials supply chains. Chinese firms recognize copper’s value from at least four perspectives. First, relative to internal industrial demand, China’s domestic production is inadequate. Second, as Chinese outbound investment has evolved to procure supply, they also are positioning themselves to capture international commodity trading opportunities. Third, Chinese outbound investment does help to enlarge the supply pie for a key raw materials essential to ongoing economic growth and for new energy systems, including those within China aimed at reducing pollution. However, China’s rush to build “green energy” scale and global market heft have fostered expansion of industrial pollutants as well as greenhouse gas emissions. Fourth, strong positions in the copper value chain can facilitate China’s larger industrial policy goals of making China-based enterprises, often “locally” controlled, indispensable hardware and technology suppliers for new energy development worldwide. These dynamics constitute the driving force behind a likely copper supercycle, as global supply comes under significant pressure from green energy ambitions.

How Much Copper is Enough?

Alternative energy systems have a high—and often, unappreciated—materials intensity, of which copper is a major constituent. For instance, every thousand battery electric vehicles (BEVs) produced can require approximately 83 metric tonnes (MT) of copper (well more than triple conventional vehicles at 23 MT), while wind turbines incorporate 3.6 MT of copper per megawatt (MW) of output, photovoltaic cells 4-to-5 MT per MW, and flywheels for pumped hydropower 0.3-to-4 MT per MW.

To quantify the relationship, 30,000 BEVs can consume as much copper as a skyscraper, like the 600,000 square meter Yi Fang Center in Shenzhen (Chinese buildings are close to 50% of global building stock). To turn over just 1/3 of the global passenger vehicle fleet (China currently comprises about 1/3 of passenger vehicles in operation) would require placing into service more than 300 million BEVs. These could collectively contain 20 million tonnes of copper, almost equal to current annual total world consumption, or about a fifth of the entire copper metal stock that analysts estimate currently sits in Chinese buildings and vehicles.

With alternative energy systems five times more copper intensive on average than their conventional counterparts, the push away from fossil fuels could strain global copper supplies, perhaps significantly. Energy transition goods will have to compete with traditional demand sources precisely as the pipeline of new copper extraction projects reaches its lowest level in the last century and risks compressing supply.

Green energy optimism and the prospects of a supply crunch helped drive copper prices to a 10-year high on the New York Mercantile Exchange in late February 2021.

Have Money, Will Travel

Chinese domestic production constitutes almost 8% of global mined copper tonnage, behind Chile (the global leader at 28%) and slightly ahead of the U.S. (about 6%). China consumes around 52% of global refined copper, about 24 million metric tonnes (MMT), and produces about 41%.

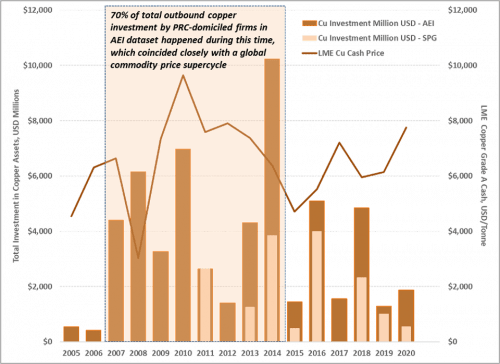

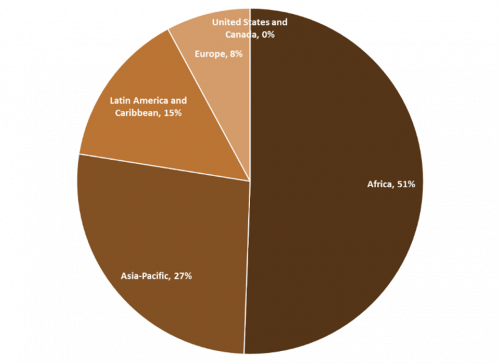

Data graciously provided by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) indicates Chinese companies invested more than $56 billion in overseas copper assets between 2005 and 2020. The AEI information compares with what S&P Global Market Intelligence reports, as shown below (Figure 1). We illustrate the distribution of Chinese copper mining investment across regions in the following pie chart (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Copper Investment by Chinese Companies, 2005-2020.

Sources: AEI Global Investment Tracker and S&P Global Market Intelligence (investment and copper price). SPG accessed via license.

Figure 2. Distribution of Chinese copper mining investment across regions

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence accessed via license.

All That Glitters is Not… Copper

A host of downsides conceals what appears initially a “victorious” move by Chinese firms to invest in a critical green energy mineral. First, what quality of assets did Chinese firms acquire when they bought mines and reserves abroad? Initial assessments in our ongoing investigation suggest that many copper-producing assets acquired by Chinese interests are in fact mature with low ore quality and often reside near the top of the global supply cost curve. In that sense, the rapid portfolio buildout that was most intense between 2007 and 2014 may be deceptive.

Here lies a second problem. Global copper market participants expect Chinese miners’ assets in various countries to be able to deliver blister and ingots should energy transition investments trigger supply/demand gaps. If Chinese copper assets fall short, a price spike could render alternative energy options less competitive with legacy fuels. In a worst case, a supply shortage could curb green energy deployments. China is attempting to substitute with aluminum to moderate domestic copper demand. That strategy could alleviate some pressure on copper but may shift the burden to aluminum supply chains.

The second problem begets a third—how does performance of Chinese miners play out in the domestic arena and then, depending on internal political and industrial policy maneuvering, with what impacts on global copper markets?

China’s Quest for New Energy Meets Global Realities

China’s 1990s “go out” policy induced Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to secure vital natural resources abroad. The push to fund copper projects abroad later coincided with several key policy initiatives that aim to position the country as a strategic source of emerging green technology. In 2015, Prime Minister Li Keqiang launched “Made in China 2025” (MIC2025), which seeks to end Chinese reliance on foreign technology by upgrading indigenous research and development (R&D) in ten key sectors, of which new vehicles and power equipment are featured as prominent targets.

MIC2025 ties into pre-existing policy initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which capitalizes on Chinese soft power to create transnational networks of economic influence. The BRI and MIC2025 play fundamental roles in the most recent Five-Year Plan (FYP) drafted during the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee meeting that concluded October 29, 2020. Delegates ratified the 14th FYP during the Two Sessions March 4-11, 2021. The 14th FYP calls for developing and leveraging control of “core technologies” in sectors such as high-speed rail, power equipment and new energy, and “localizing technology and critical production in China, including through import substitution.”

As China pledges to peak its carbon dioxide emission before 2030, it has positioned goals set forth in the 14th FYP and MIC2025 as critical to realizing this optimistic reduction.

Copper is a vital resource to facilitate output expansion in multiple MIC2025 target sectors. Any shortcomings in Chinese miners’ performance abroad (tonnage output and financial returns) will thus likely reverberate domestically—particularly if the copper rush fails to yield the expected returns on investment.

Global Performance, Locally Driven

Competition among ambitious urban leaderships in China stands to amplify the outcomes.

For instance, Nanjing, former capital of the Six Dynasties and the Republic of China, is one of the most active cities in creating an R&D ecosystem as it vies to claim its place as a capital of technological innovation. Nanjing is a major node in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, the driving economic force generating more than 40% of China’s GDP. During a domestic inspection tour in October 2020, President Xi Jinping underscored the region’s strategic importance.

Minmetals president and MCC Chairman Guo Wenqing made a notable appearance at the 2018 conference in Nanjing, symbolizing the mining sector’s involvement in locally led drives for emerging technology R&D. Under its “Two Landings and One Integration” project, the city oversaw establishment of the Nanjing Jiekefeng Environmental Protection Technology and Equipment Research Institute in June 2018. The Institute has already hatched 23 tech-based enterprises and contracted a total amount of about 25 million yuan (around US$ 3.8 million), according to school dean Xu Haitao. The Future Network Development Conference launched in 2017 attracts top R&D talent and investment and lays out policies conducive to fostering innovation.

What’s Next?

The mid-2000s copper price spike augmented the case for vertical integration. The price collapse in 2015 and BRI imperatives fueled consolidation of equity interests with assertion of central control in some cases. Now, Chinese SOEs will be benchmarked against multinational miners amidst financial pressure on the global industry and assorted business risks, not least the pandemic. Any lack of competitiveness eventually will come to bite. As the Nanjing example shows, ramifications in China extend far beyond corporate balance sheets. China’s industrial policy, centrally encouraged but locally executed to maximize control over raw material value chains, may collide with tough realities as it seeks positioning as the indispensable player in the energy transition.

This post originally appeared in the Forbes blog on April 5, 2021.